Cirque Physio’s Dr. Jen Crane Lays It All Out with Training Tips

Dr. Jen Crane has many credentials beyond her doctorate in physical therapy. Among other things, she is a board certified orthopedic specialist and a certified athletic trainer who is licensed to practice physical therapy in California, USA. But she is also an educator (who travels the world teaching workshops), an author, a blogger (Cirque Physio)and a practicing circus artist focusing on dance trapeze, aerial straps, and hand balancing.

She has spent her career working with athletes and artists, and is well known for her non-traditional approach to physiotherapy. Her mission is to empower circus practitioners (through multiple channels) with the tools they need to focus on injury prevention and performance optimization. In 2015, she worked as a physiotherapist living in China with the Chinese Olympic Teams in preparation for the Rio 2016 Olympics. Now, in addition to maintaining her practice in California, she works on a contractual basis with Cirque Du Soleil as a physiotherapist in their performance medicine department.

I had the good fortune to sit down together over a cup of tea and discuss her fascinating and practical approach to injury prevention and performance optimization.

Kim Campbell: You have these three hats that you wear according to your website; orthopedic specialist, athletic trainer and physical therapist. Do these all coincide in one job or this three separate things that you do?

Jen Crane:The “alphabet soup” at the end of the names are always a little bit confusing and I feel like that’s a really good place to delve in, as they can mean a lot of different things. The ‘PT’ indicates that I am a licensed physical therapist, this is called the ‘designator.’ The, ‘DPT’ is my terminal degree, which stands for doctorate in physical therapy. In the US, all physical therapy schools are doctorate degrees, but this differs abroad. The ‘OCS’ indicates that I am a board certified orthopedic specialist- this means means that I took an extra year after I got my doctorate to sub-specialized in sports in orthopedics. Finally, ATC means I am a certified athletic trainer, which is what I studied in undergrad. Athletic trainers are not the same as personal trainers in a gym, an ATC is a sports medicine professional who specializes in injury prevention, assessment, management, treatment and rehabilitation specific to one particular sports team. They are highly trained in acute and emergency injury management- they’re the ones who run on the field when someone gets injured during a sporting event. Basically, my alphabet soup means that my educational background is heavily focused on sports and orthopedics, as well as acute injury management.

KC: What interested you about working with circus bodies?

JC: I started working with circus artists after I discovered circus, on a personal level. The day after I took the board exam for my orthopedic specialty certification, I decided that I needed a hobby because I had been studying for the past year, and now found myself with time on my hands! So, I found a rock climbing gym that was really close to where I lived in Texas at the time. When I walked in, I saw two girls on aerial silks, and I decided that looked much cooler than rock climbing. From that day, I was all in: aerial silks, trapeze, and hand-balancing. After about a year, I decided to move to San Francisco to further my circus training.

In San Francisco, I started to realize the cultural issue of chronic injury in circus arts: it seemed like so many of my circus-classmates were always hurt, and yet, they had no reliable healthcare providers to turn to who fully understood the demands that circus puts on our bodies. If they did go see a PT, the story that I kept hearing was that the PT would just tell them to stop training, or that they were going to break themselves. Often, these PT’s would do all of the “normal” strength and flexibility tests, which these injured artists would “pass” by “normal” standards. This is quite confusing for a PT who doesn’t understand circus, and so they would often just throw their hands up in the air and tell them they didn’t know what to do with them. I thought that that was really unacceptable just across the board, and wanted to do something about it. After I heard this same story for long enough, I opened a small physical therapy practice in San Francisco. It was the best decision I ever made — it’s completely changed everything about my life, and I cannot imagine a more deeply fulfilling career.

KC: Is working with a circus body different than an athletic body?

JC: It is so different! It’s interesting, because prior to circus, my professional background was with high level mainstream sports– from football to gymnasts to dancers. You would think that there are a lot of similarities, and there are some, but circus artists just demand such different skill sets and flexibility and strength from their bodies than every other athlete. For me, it helps so much that I do circus. To be able to experience the various specialties and apparatuses first hand greatly informs my diagnostic and treatment approach for this demographic.

KC: Do aerialists have more injuries than acrobats?

JC: In my experience, yes, but in general, I do see more aerialists than acrobats — so this might just be a function of aerial becoming more mainstream in the recent past. Its interesting, though, because (in my opinion), from a career-longevity standpoint, I would say that aerial — if done with proper technique — has the potential to be more sustainable longer than acrobatics. The repeated impact involved in acrobatics tends to lead to more long-term issues, whereas aerial is largely non-impact and strength-based. This can be great for our bodies as they age, especially from a bone-density standpoint. So as an aerialist, in general, you can safely train and perform for quite a lot longer than you can as an acrobat just because of the impact.

KC: What differences are there between what type of injuries aerialists and acrobats tend to get?

Shoulder injuries for aerialists, and ankle/knee injuries for acrobats. In my experience, shoulder injuries in aerialists tend to be perpetuated by the cuing that we use with respect to shoulder position. Often, we are encouraged to bring our shoulders down and back while hanging on straight arms. I think the roots of this must come from the desired aesthetic in dance/ballet– as a culture, we think that the shoulders down and back when our arms are overhead gives us this long neck and looks nicer, even though it puts the shoulder in a biomechanically disadvantageous position. I see a lot of shoulder injuries in aerialists that are related to this cueing. Interestingly, cueing in acrobatics for shoulder position is totally different. If you’re doing anything with your arms overhead, handstands or tumbling, you’re taught to be fully elevated/shrugged: this is a very safe and stable shoulder position.

KC: What’s your top injury prevention tip?

JC: A lot of injuries come from overtraining in circus because we don’t have seasons. In mainstream sports, there is an on season and an off season, which builds in a really nice periodization to training. During pre-season, you ramp up training for competitive season. In competitive season, they stop adding load, and switch to maintenance mode to preserve strength and energy for games. Then they de-load and recover during the off season. It allows for a great ebb and flow that we just don’t have in circus, whether we’re talking about hobbyists who take session-enrolled classes, or professional artists who are doing gigs or contract work. There’s also this mentality of #circuseverydamnday, which doesn’t exactly facilitate adequate recovery in our culture!

KC: And circus seems to attract the kind of person that wants to train all the time.

JC: Yes, and then that leads to a lot of overuse injuries that may not be there if they trained on a more periodic schedule.

KC: So what periodic schedule do you recommend?

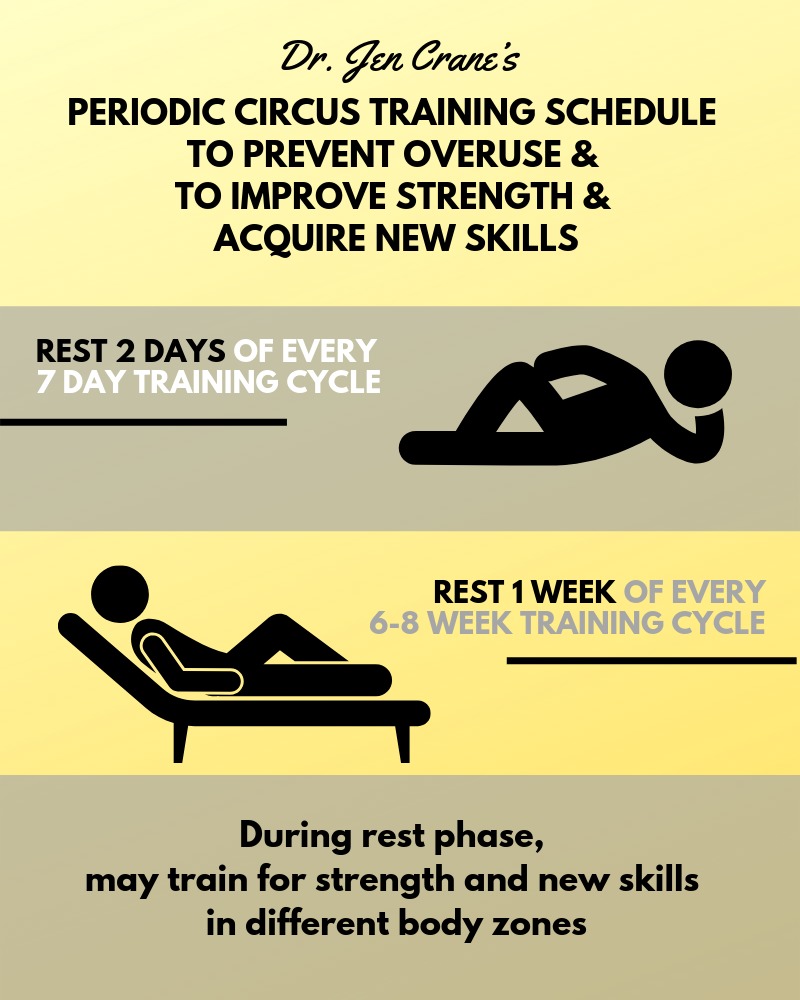

JC: Honestly, it depends so much on the individual artist, their lifestyle, and their goals – but its helpful to at least give a starting point to adjust from. My very general recommendation for artists who are training with the goal of improving strength or acquiring new skills is to take two recovery days per week. Then, for every six to ten weeks of training, take one full week off of your primary specialty.

So if we’re looking at a two month period of time every week in that two month period, you’re having two days off per week and then at the end of that to six to ten weeks, you take one week off.

KC: And at that time, is it okay to just change your focus to another training area if you’re very goal-driven?

JC: It depends. So if the person is an aerialist and a hand balancer, then generally what I’ll tell them is whatever body part you mostly use in your specialty, give that body part a rest. So for aerialists, don’t do much with your shoulders. Juggling is probably fine, because it’s a lot different and less intense. But I’ll say for an aerialist, go take dance classes, go for a walk, go for a bike ride, use your legs. So whatever the opposite is that you usually use. Do that. Which is always met with weeping and gnashing of teeth.

KC: Do you have other tips that are equally important or do you think that’s the biggest piece of advice circus artists need right now?

JC: I think right now, in our circus culture, that’s what needs to happen because that has implications across all injuries regardless of whether it is a hip injury or a shoulder injury.

KC: So what do you recommend to young circus artists who can’t afford to hire a physical therapist or who don’t have insurance? What is your advice to them to get help?

JC: There are a lot of good resources that are free right now. That’s why I have my blog. My blog has all of the information that I talk about all of the time…about recovery and shoulder position and creating this periodization and all of that. The thing that’s hard is, if you don’t want to spend money, you have to make sure that the information is from someone who is qualified to be giving that type of content.

There’s so much pseudoscience, especially in circus, so it’s hard if you’re going to take advice from somebody and if the advice is free, make sure that they have a license or a degree or something equivocal in that field.

KC: Can you tell us a little bit about your books and how people should use them?

JC: MyFLEX is a self-paced online educational course and customized flexibility program. There are two main parts: the first part is a guided, total body self-assessment that pinpoints and quantifies the structures that are currently limiting the students progress towards leg and back flexibility. The assessment is supplemented with dozens of educational videos that teach flexibility theory and biomechanics as applied to performing arts. Then, once the student has submitted their self assessment, I use the data from these tests to create their customized flexibility program, which is comprised of two separate video libraries: one instructional exercise library, which has long form videos of proper technique for each drill in their program, and then a follow along, playlist-style video where the student presses play and stretches along with video-Jen! The idea behind the program is to discover what structures are limiting your flexibility, and then address those specifically– instead of using a cookie-cutter, shotgun approach. Because of this, there is also a huge injury prevention component to MyFLEX, to avoid stretching-related injuries.

KC: What’s your favorite workshop to teach?

JC: Probably either my shoulder or low back injury prevention workshops. I like these a lot because of the way that I’ve structured them: as multi-part movement assessments. Each workshop has a five-part screen based on different components of strength, flexibility, and control that we need as circus artists that other physical therapists wouldn’t necessarily know we need. Its for those instances when a circus artist hurts their shoulder, goes to a PT, and the PT tests their strength and range of motion and says “You are within normal limits. I don’t know what to do with you.” Circus artists have such different strength and flexibility requirements, so these workshops are much more nuanced with the movement assessments.

Every test in the assessment is a pass/fail test. I demonstrate the test, talk about what it looks at and why it’s relevant to circus. Then, the students test each other and are assigned a pass/fail score. After each test, I demonstrate and teach exercises that will help improve that component of the test and therefore decrease their injury risk. So by the end of the workshops, students have a solid grasp on what strength and flexibility components they need to address, and what exercises to do to decrease their injury risk. They also are equipped with an understanding of how to re-test themselves after a month or two, which is a very motivating way to measure progress.

How do you make sure that you’re addressing that component of rehab? Because it’s so important and you’re not going to address that by doing theraband exercises.

KC: What other issues would you like to explore in circus physical therapy?

JC: I’m really interested in bringing in more of the sports psychology like we were talking about with recovery and periodization…and bringing in a little bit more of a holistic view to circus. I think there are a lot of physical therapists that can evaluate and treat injuries, but especially in circus, there’s such a big impact from psychosocial components of training and the psychology of being injured when you’re a professional artist. How do you make sure that you’re addressing that component of rehab? Because it’s so important, and you’re not going to address that by doing theraband exercises!

KC: Do you foresee a future or a need right now for every school to have a physio/PT on staff?

JC: I mean, that’s the dream. I don’t know how realistic that is. And I often think it depends, because a lot of bigger circus schools, like ENC and NICA, all have physios on staff. They have to. Some of the smaller schools don’t necessarily, but I think that it would be great at least to have a network of providers that are good at treating circus artists.

All photos provided courtesy of Dr. Jen Crane...

Do you have a story to share? Submit your news story, article or press release.