“Female Aerialists in the 1920s and Early 1930s” is a Circus Library Must-Have

If early 1900s western circus history was a circus act, I would hire it. The stories have all the earmarks of a quintessential crowd-pleaser: drama! romance! danger! comedy! Near escapes, outright catastrophes, steadfast family bonds, unwavering dedication to one’s art. This sensationalism is what hooked me as a young academic, but as quickly as I was dazzled, my enthusiasm dulled. I encountered the same stories over and over. Consuming the saccharine and sentimental plots on repeat was like snacking on an endless yarn of cotton candy – I became queasy at reading (again) about Philip Astley. I craved to know about circus as a cultural force that steered western society, politics, and national identity. A few authors fed me well, most notably Janet Davis and Peta Tait. Kate Holmes’ recent publication,Female Aerialists in the 1920s and Early 1930s: Femininity, Celebrity and Glamour, has left me fully satisfied. It is the perfect cocktail: equal parts scrupulous circus research, comprehensive cultural context, and a wise and fair contestation of ingrained nostalgia. It is a must-read for present-day artists, fans, students, and academics alike. It is an essential resource for the well-informed aerialist. For they are the embodied legacy of aerial action, and this is a piece of their history. It raises the bar for how circus history is told. Move over, pink lemonade! Holmes is serving up the new champagne of circus academics.

As a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Exeter, Holmes’s research focuses on aerial performance practice and its history. Driven by wanting to know more about her own amateur practice as an aerialist specializing in static trapeze, her research is centered on the embodied experience of aerial performance and circus. Holmes’s approach to history centers on reconstructing the details of acts in order to understand how audiences experienced performers’ acts and the meaning of these performances. She does this by considering issues of celebrity, gender, spatial practices, kinaesthetic theory, and by placing performances in the context of female physical culture, film, and sport stars’ representations.Female Aerialists in the 1920s and Early 1930s expands and updates research she undertook during her PhD at the University of Exeter. It is her first book, and it is more than apropos that it be highlighted today, International Women’s Day!

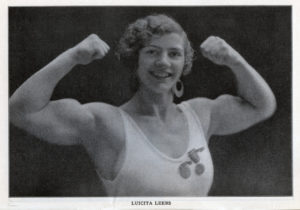

In a jam-packed intro, five chapters, and conclusion, Holmes brings to life the US and UK’s most celebrated female aerialists of the interwar period. Lillian Leitzel and Luisita Leers take the spotlight with Clara Curtain, Vera Bruce, and Winnie Colleano radiant in the limelight. Holmes has smartly crafted consecutive chapters that build upon one another, but they are also complete as stand-alone essays – a gift to readers with short attention spans or anyone wishing to incorporate a singular portion of the book into a curriculum.

By spanning ‘the pond’ from New York’s Madison Square Garden to London’s Palladium, Holmes takes her reader on a journey that reveals cultural commonalities and differences between the two nations through aerial arts. Each facet of Leers and Leitzel’s performance – costuming, lighting, staging, the physical movement, and showmanship – are given rigorous attention. Holmes extends her analysis to the decor of performance venues, ticket prices, seating arrangements, and marketing materials. All this is contextualized by the status, role, and shifting cultural views about able-bodied white women during these years. Her source materials are similarly multifaceted, creating a satisfying three-dimensional analysis. As she states, “Examining the cultural significance of Leitzel and the other performers in this book is like viewing them as a series of reflected images because it is impossible to see them exactly as they saw themselves or as audience members saw them… Each mirror provides a slightly different perspective on the past that generates different meanings from the source material” (3). Holmes’s interpretation of these materials is clear, her writing is approachable, and while a background in western circus history will certainly aid the reader, no prior knowledge is needed to appreciate the text.

Holmes is able to make the intangible concepts of nostalgia, glamor, and celebrity concrete to her reader. She writes, “The circus histories most commonly retold become the ones that embody nostalgia… The risk in uncritically accepting timelines of popularity is that this nostalgic thinking forgets the important legacy of artists such as Leers and Leitzel” (10). Her expertise as a writer shines in her ability to preserve these performers’ stories with a sense of wonder while employing exacting research to clear away the nostalgia that has clouded other recorded histories. She corrects previous interpretations calmly, precisely, factually – not always gently, but never condescendingly. Similarly, Holmes’s meticulous investigation of the time period helps to pin down how Leers and Leitzel contributed to western ideals of glamor and celebrity. Because these concepts are subjective, Holmes notes that it is necessary to analyze through “particular moments and cultural products” (52). Holmes identifies the image of the female aerialist as a cultural product, and performed actions as artifacts through which the western concept of glamor, celebrity, and femininity were defined. Holmes deftly presents Leers and Leitzel’s bodies and actions as cultural evidence, but she does so without objectifying them. They maintain their humanity, autonomy and power.

To enrich her research, Holmes becomes her own expert witness by applying her personal kinesthetic knowledge of aerial to the actions, labor, dynamism, and showmanship of her subjects. She is able to analyze footage of Leers and Leitzel’s act from the inside out. She demystifies their actions and creates an intimacy and heightened appreciation inaccessible through anatomical analysis alone. By providing embodied, sensorial descriptions, Holmes provides her reader with a multi-dimensional experience of aerial action – an imperative means of performance analysis as the genre evolves.

Virtuosity is being contested by contemporary creators and therefore changing how “circus” is inscribed on performing bodies. If today’s physical experience of circus becomes far-flung from ancestral experience, we lose a vital thread of circus evidence: kinesthetic, embodied knowledge. In other words, if performers stop learning muscle grinds (elbow rolls) on the trapeze, no one will ever know what Leer’s finale felt like. This makes Holmes’s book an important example of how pairing embodied knowledge, cultural analysis, and performance theory is crucial to holistically preserve the legacy of circus through art and academics.

By narrowing her research to a short time period and two white, superstar female aerialists, Holmes has created an academic catch-22. These boundaries allow for a phenomenal deep dive; Holmes clearly left no stone unturned, no newspaper clipping unread, no photograph unseen. This thoroughness makes her a trustworthy author. A reader can relax into the fact that they are getting the most pertinent information. Conversely, when reading texts with such a narrow lens, a reeling curiosity is sparked in me. I found myself often thinking, What about… western female Black performers? Asian performers? Disabled performers? The masses of women that danced in group numbers? Female animal trainers? And by extension, the women who, for a myriad of reasons, could not participate in the fashion, hobbies, or visibility necessary to fulfill the image of the modern girl or the New Woman and were therefore excluded from the entire cultural movement? More often than not, within a page turn, Holmes nodded at my questions and gave me just enough information to let me know that she, too, knew these were important lines of inquiry. And here is where the catch-22 transforms from a stagnant loop into an explosion of opportunity. Because Holmes’s tapered analysis allows for depth and an exhaustion of evidence, it also proves that each What about… inquiry deserves its own meticulous research, for each has a rich and important history.

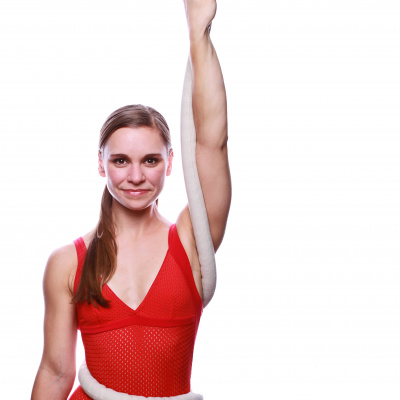

Leers and Leitzel’s stories are a century old. This chronological distance and the fact that, at first glance, they are cotton candy sensational tales with their share of danger! romance! and drama!, puts them at high risk for being sugar coated in nostalgia. I believe that in order to stay appetizing, history must be presented as more than a linear story with a beginning, middle, and end. It must be illustrated with why and how the events took place; it must be animated by the repercussions it has on current culture. Life is then breathed into history when it is recognized in present day embodied actions. Holmes does just this. She concludes her book by illuminating the stark connections between Leers, Leitzel, and P!nk, a pop star known for doing her own aerial work and, through her celebrity, pushing the boundaries of femininity just as Leers and Leitzle did. The lineage of celebrity, glamor, and femininity are clear.

Leers and Leitzel’s stories are a century old. This chronological distance and the fact that, at first glance, they are cotton candy sensational tales with their share of danger! romance! and drama!, puts them at high risk for being sugar coated in nostalgia. I believe that in order to stay appetizing, history must be presented as more than a linear story with a beginning, middle, and end. It must be illustrated with why and how the events took place; it must be animated by the repercussions it has on current culture. Life is then breathed into history when it is recognized in present day embodied actions. Holmes does just this. She concludes her book by illuminating the stark connections between Leers, Leitzel, and P!nk, a pop star known for doing her own aerial work and, through her celebrity, pushing the boundaries of femininity just as Leers and Leitzle did. The lineage of celebrity, glamor, and femininity are clear.

P!nk is a singular, highly visible example of how this particular history is embodied in current western culture. There are likely thousands of aerialists whose current practice reflect and are therefore descendents of Leers and Leitzel’s legacy, and as iconic figures these women reshaped the definition of feminine. Their stories – which Holmes has meticulously illustrated, animated, and brought to life this history for her readers with the utmost care – have value in both the performance and academic communities. It is my hope that future publications match Holmes’s dedication to thoroughness and criticality, so that we may continue to fill our libraries with robust and honest versions of circus history.

.

...Do you have a story to share? Submit your news story, article or press release.