How the Contemporary Taiwanese Circus Artist Innovates: Tsiú-tsiān

As part of our continued exploration of the Taiwanese circus industry, question-setter Stella Tsai and interviewer Wen-Ling Lui recapture a discussion from the last edition of the DuMaXi circus platform. Three industry experts weigh in about circus history, juggling tricks and ideals inspired by daily life in Taiwan— and how contemporary Taiwanese circus artists lead the art form forward.

Whether in traditional juggling or contemporary circus, there are many moments or situations in our lives that are related to the circus, and many props and tricks that we derive from it.

At the latest edition of the DuMaXi circus platform, we invited Ms. Ching-Lan Chang (hereinafter referred to as Ching-Lan), a teacher from the Lee Tong Hua Acrobatics Troupe at Taiwan’s National College of Performing Arts; and Mr. Hsing-Ho Chen and Ms. Yu-Lun Chiang (hereinafter referred to as Hsing-Ho and Yu-Lun), the founders of Hsingho Co., Ltd. & HoooH, to join a panel and share how things from their everyday lives inspire them to innovate and give old objects new life through circus. Their answers were as follows:

Wen-Ling: What was the first activity you ever did that, looking back, you realize was related to circus?

Ching-Lan: I was raised in a military dependents’ village. Children in our village would string together rubber bands and play jump rope in groups of three or four, slowly rising from the lowest height and adding in more difficult skills, such as jumping over the rope without touching it, scissor feet, doing flips, and so on. All this is somewhat similar to the forms of skill development in acrobatics.

Yu-Lun: My family runs a lumber business. Our household usually has a lot of wood piled in the corner. I was the only child in my family, so I had to find ways to kill time. Every day, I would design a running and jumping route for myself according to the shape of that day’s wood arrangement. Now that I think about it, that was basically parkour!

Hsing-Ho: When I was a kid, I practiced jumping from my bed to my night table, just for fun. In fact, even children without any acrobatics training will naturally look for places with a height difference to jump off of or walk the line, and try to imitate the cool things they have seen someone else do. Our most instinctual motivation is actually the “eagerness to play”— people will challenge themselves subconsciously in this way.

Wen-Ling: In traditional juggling and acrobatics, what props or tricks are derived from daily life?

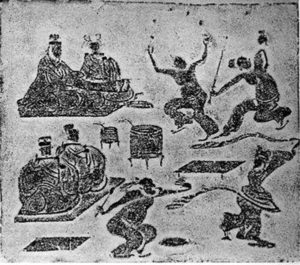

Ching-Lan:In fact, looking back at the history of acrobatics in China, techniques have often been created from the equipment we use in life and games. For example, “Nòng Wán” was a type of Ancient Chinese juggling that involved throwing and playing with mud balls, just like throwing sandbags. Later on, it developed into different forms of throwing, catching, and grabbing. In addition, performance techniques such as plate spinning or the Chinese pole are all developed with everyday objects.

Hsing-Ho: I have researched the history of juggling tricks in various civilizations, such as Chinese foot juggling, a technique of lying down and kicking with one’s feet. Similar movements were performed in the Aztec civilization of Mexico; Ancient Egyptian wall paintings depict ball tossing and cup stacking, and Catalans did rituals of human stacking in celebrations. All these civilizations have similar movements to more modern techniques, echoing the idea that, as Ching-Lan described, acrobatics techniques develop from games. You will also find that everything starts from the human need to “move,” whether it is done for games, hunting, rituals, farming, or other daily needs. When these movements are done with more skill, they naturally become a kind of performance.

Yu-Lun: There is also the meteor hammer seen in Hong Kong films, which was historically used as a real weapon. Nowadays it is often used as a prop in circuses.

Hsing-Ho: The birth of the Russian ball is said to have happened when someone who disliked cereal had the idea to put his cereal inside a ball, to keep the ball from rolling when it fell to the ground; it thus evolved into a prop suitable for performances. There are many more legends and stories like that—all these things are inspired by life.

Wen-Ling: What are some ways that contemporary circus performers have given new purpose to everyday objects?

Hsing-Ho: Recently, I have seen some circus artists using the big, iron ring of a Cyr Wheel as a hula hoop instead. It gives a whole new meaning to that equipment.

Yu-Lun: I once saw an act with two performers dancing on a floor in the middle of the venue. We all think that the floor is something stable; it will not move. But in this act, the floor itself became a major part of it: while the dancers move, the floor is also floating up around them. It is easy to take for granted that the floor is just a nobody in performances, but here, it was almost a performer in and of itself. That is another way that everyday objects can be used in ways that break from our established impressions of them.

Hsing-Ho: Not only does this kind of thing happen in contemporary circus, but also, many classic acrobatic props have emerged by artists constantly breaking the accepted “rules” of how to use them. As long as someone has done a new exploration with a tool or skill and then followed that path all the way down to where it leads, eventually, that style will itself become classical. And then new people will be saying, “Hey, should we try something else?” Then even more new forms of expression will emerge, whether they use everyday objects or equipment developed over time.

Wen-Ling: How does an artist’s life inspire their creativity?

Ching-Lan: In recent years, when guiding students to create, we teachers hope that they will develop work from their own life experiences or feelings, and then extend that vision to the audience through the use of props. Drawing from life, you will find that there are many possible ways to use the same items. I myself was trained in a very traditional way. During my time as a student, I had to follow all my teacher’s orders. There was no chance for me to express my own opinion.

Students today have a certain model of physical and technical training, but when it comes to adding different performance elements, they should open their eyes and ears. They need to observe things around them, listen, and keep thinking all the time during their training. Only by changing and dismantling ourselves will we be able to make breakthroughs in developing new props and performances. In that way, we can discover more possibilities to connect with the audience and, in a sense, build a bridge between the artist’s and the non-artist’s worlds.

Yu-Lun: I used to think an artist’s sensitivity to life was crucial to their creativity, but now I think that it is more important to have the ability to think independently. What are your feelings, and how do you interpret them? How will you use them?

Hsing-Ho: That’s another important thing: whether you have the confidence to believe in what you feel. If you don’t have the confidence, you will follow in others’ tracks; if you have the confidence, you will be able to do your own exploration and see different ways of presenting things. For example, when I was starting out in acrobatics, I always tried to imitate other people. I thought that I had to follow a certain learning method if I wanted to have a real chance as an acrobat.

On my first trip to Europe, I always asked other performers, “How did you do that act? Did you learn something special?” And most of the time, they would respond, “I didn’t learn it, I invented it myself. I just thought it would look beautiful on stage.” I didn’t even believe them. It took me many years to believe that kind of creativity was really possible. But when you feel the beauty in life, and you believe in it, you have the opportunity to create something different out of it.

In the past, whenever I heard someone say that acrobatics is an art that’s meant to show the power and beauty of the human body by challenging its limitations, I would think, “Is that the only point of doing acrobatics? Isn’t there something more to it than just exploring our potential?” I’ve since realized that, no, it is really like that, but that this purpose is something very crucial. Whether we are athletes, scientists, or circus performers, we are always exploring what else we can do.

Wen-Ling: How do you see the balance between traditional training and contemporary juggling/circus?

Ching-Lan: In terms of my teaching environment, I keep reinventing my teaching style to try and connect better with my students. I hope that my students will be inspired, and then be willing to commit themselves to the challenge because they like it. But first, I want them to spend the time, energy, and physical endurance it takes to know that they are willing to keep going down this path.

After all, I grew up under the traditional teachings; I was not exposed to modern forms of circus until I was 25 or 26 years old. Now as a teacher, I need to find a new approach. I have to overcome my past experiences and learn and grow with my students. However, I still believe that “quantity leads to quality.” Learning and teaching both come down to repetition, and only when the quantity of our training reaches a certain level will we have the opportunity to make qualitative adjustments to our methods.

Regarding the balance between traditional and contemporary circus… I think the most important thing for a performer is that they are willing to change up their style and integrate many techniques, both old and new. It is impossible to achieve a true balance between modernity and tradition, but they should still be willing to try.

Hsing-Ho: I agree with Ching-Lan. Just by talking to people from different backgrounds and going to various events, you will start to see the world differently as an artist, and move forward in the direction you believe is right. Where people want to go, the market they want to be in, and how they can survive in it are all considerations that affect the balance they come to. If one can survive by discussing concepts, then one does not need traditional training in physical fitness.

Yu-Lun: I don’t have an answer to this point, but I have always felt that technique is a very important element, both in circus and in juggling: without technique, it is not circus. My theory is that if you are Taiwanese trained, you will have the aesthetics and performance style of a Taiwanese artist, just like how many European performers are now trained in contemporary circus schools. Maybe they will want to revive the traditional performance style, but even so, the works that they produce will still have a contemporary look and feel to them.

Wen-Ling: Please recommend a circus technique that the general public can play and practice on their own.

Hsing-Ho: They can try anything, from yoga to juggling, to making paper airplanes. Just throwing an airplane straight or roundabout requires a lot of skill, and can be practiced for a long time.

Ching-Lan: Oranges and tangerines both make very good juggling props, and many people can find them at home. They can play juggling games with their elders to help train the elderly’s reflexes. There are many similar things in life they can explore.

Yu-Lun: I think circus and acrobatics give you this kind of tickling feeling in the heart—a feeling like you’re fighting against death. If people want to experience that feeling immediately, they can go on a roller coaster, or simply stand on a high balcony. People can find circus and acrobatics at any time and anywhere in their lives, as long as they are willing to open their hearts to the experience and try.

Credit to Wen-Ling Liu for the written transcript. Images shared by Martina Lin. Portraits of panelists credited to Pei-Yu Hung....

Do you have a story to share? Submit your news story, article or press release.

![Yu-Lun Chiang, Taiwanese acrobat and co-founder of [], smiles for the camera. She has short hair and a yellow shirt](https://circustalk.com/news/app/uploads/2022/04/circus-Yu-Lun-Chiang-DuMaXi-Taiwanese-Circus-Platform-circustalk-800x445.jpeg)