Sacred Arts Offers an Interdisciplinary Research Method for Circus and Beyond

This past March, Ben Yehuda Presspublished Under One Tent: Circus, Judaism and Bible, edited by Professor Ora Horn Prouser, Cantor Michael Kasper, and myself. The genesis of the book was a desire to discuss an academic method that was developed at the Academy for Jewish Religion called Sacred Arts. In the book we focus on how Sacred Arts works and has been successful using circus and dance to study sacred texts. The book pairs the explication of Sacred Arts with fascinating research by a group of international academics. While the book, for the most part, has a Jewish or religious spin to it, it also provides history, theory, and pedagogy that would be beneficial for any circademic.

Sacred Arts is a method of using the arts to study text. It is not using text as a jumping off point to make art, nor is it using art as a reference point (among others) of interpretations of a text. It is my and the other editors’ belief that Sacred Arts should be seen as another academic method of studying texts equal to other approaches such as literary criticism, gender studies, or critical theory.

We have studied a number of texts through a range of circus arts including tightwire, juggling, human pyramids, and double trapeze. Unfortunately, Sacred Arts is really best understood by actually doing it! To help, however, I will provide one example from a Sacred Arts workshop that I think epitomizes the method.

In this workshop, we were studying the Garden of Eden narrative. As in any circus Sacred Arts (1) experience, we first studied the text “traditionally”— sitting at a table with fellow students discussing and dissecting the text. Following that, we learned some circus skills, and then tried to bring the two together: we attempted to embody the text via the circus skills. This particular time, we built a human pyramid with the hope that the experience of doing pyramids would inform us on the text. It so happened that among the participants in this workshop were a number of parents and their children. One mother was specifically researching God’s role in the narrative and was attempting to embody God as part of her text analysis. During the pyramid, she felt a deep sense of parental anxiety. While connecting it back to the text, she picked up on multiple moments of anxiety. This included the moment in the narrative when Adam and Eve are hiding their nudity in the garden and God asks them, “Where are you?” (Genesis 3:9). Prior to this workshop, she read this as a loaded question, as if God already knew the answer. After this workshop, she believed it was a panicked, anxious question. (2)

This story provides a lot of information about Sacred Arts.

First, circus Sacred Arts is not about making art, or any sort of mimetic approach to circus. It is specifically about the experience of doing circus as a point of research. Moreover, it is the fact that bodily information is just as credible and able to drive one’s research similarly to a cognitive thought alone. This participant’s anxiety inspiring a different reading of a text is a circus Sacred Arts moment.

Second, we approach God as another character in the text that can be a source of analysis. Many of our participants have felt uncomfortable with the idea of embodying God, or trying to reflect on the perceptions of God. That said, we find it a fruitful area of research, such as the example above that humanizes God.

Third, all Sacred Arts readings must be able to be legitimized by the text. In the Jewish approach to biblical study,two ways of categorizing readings are peshat, a contextual reading, vs. drash, an interpretive reading. In the practice of Sacred Arts, we are looking for the peshat, a reading that can be fully supported by the language of the text rather than how someone feels inspired by the text. It is also important to note that there can be mutually exclusivepeshatreadings,e.g. the omniscient God as opposed to the panicked, anxious God. I believe there is enough evidence in the text to support both readings.

There are a number of chapters in Under One Tent dedicated to corroborating the Sacred Art method in different manners. They include connecting circus and religion, connecting circus to Jewish thought and history, connecting circus and dance to the classroom, embodiment theory, and applied embodied education.

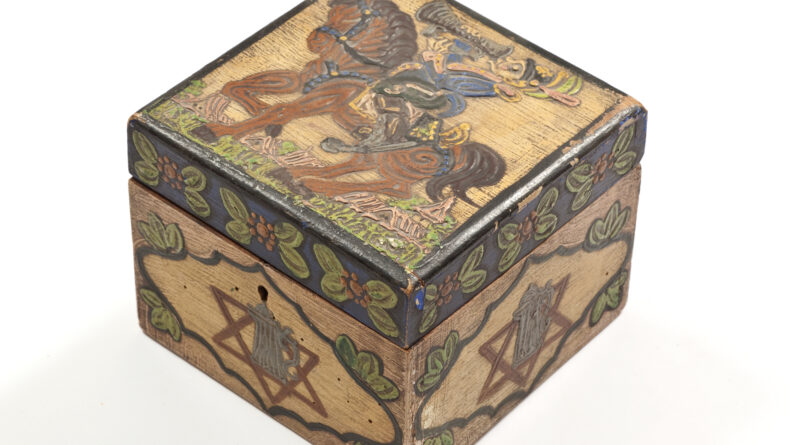

Throughout the book, the role of circus in Jewish life is shown via artwork by Jewish artists with a circus subject. There is artwork from Chagall, Man Ray, circus posters, Azoulay, and others.

/Click on image to open gallery/

The book begins with a focus on circus and religious thought. Professor Camilla Damkjær presents an inner dialogue and analysis of her interaction and development as a practitioner of Ashtangi yoga. Calling herself an “Ambivalent Ashtangi,” she gives voice to an understanding of the role of movement in personal development. Drawing on her personal experience as a circus artist, philosopher, and academic, she takes us on a journey placing physical practice at the center of her academic, emotional, and spiritual growth.

Jessica Hentoff, a leader in the social circus field, builds on this theme by writing about how she puts circus arts at the center of her worktoward tikkun olam, the Jewish term for social justice. She tells the story of building Circus Harmony and its predecessor programs. These programs bring together youth from different communities that, if not for their circus work, would have not interacted. She then discusses how these programs expanded to become an international force; they joined Israeli Jews and Arabs who used circus arts as a conflict resolution method to work toward peace.

Jessica Hentoff, a leader in the social circus field, builds on this theme by writing about how she puts circus arts at the center of her worktoward tikkun olam, the Jewish term for social justice. She tells the story of building Circus Harmony and its predecessor programs. These programs bring together youth from different communities that, if not for their circus work, would have not interacted. She then discusses how these programs expanded to become an international force; they joined Israeli Jews and Arabs who used circus arts as a conflict resolution method to work toward peace.

The next section explores how the history of circus arts is deeply intertwined with the Jewish experience – and it is also just interesting circus history! Juggler and historian Thom Wall begins the section with the history of juggling in antiquity, focusing on ancient Egypt and ancient Babylonia, among other locations. He cites references to juggling from rabbinic literature and explores a possible reference to juggling in the Hebrew Bible itself.Wall’s chapter in Under One Tent combines information from his book Juggling: From Antiquity to the Middle Ages, as well as some new research.

Artist/researchers Stav Meishar and Roxana Küwan’s chapters focus on their research of circus Jews in Germany before and during the time of the Holocaust. The history of Jews in circus, however, goes beyond this major historical event. Jews have had a place in circus history starting with contemporaries of Philip Astley to today. The chapter dedicated to highlighting Jews in circus history aims to make the point that bringing circus and Jewish thought or texts together is very much in keeping with Jewish life.

After these chapters about circus history and the role of physical movement in personal development, the book moves on to theory and practice of movement in study.

Professor Lori Wynters opens up the world of embodiment theory. She explicates the concept and explains how thinking with our bodies is a part of our very make-up. She relates embodiment theory to Jewish life, ritual, and learning, and she provides a model for bringing embodiment theory into the classroom. We see embodiment as, in some ways, the base upon which Sacred Arts stands, limiting the separation between mind and body and pushing the limits of body-based learning. Her chapter does a great job connecting embodiment theory to Jewish thought and providing fresh perspectives on embodiment as a whole.

Next, a few chapters–written by thoughtful educators–all give specific examples of how they have brought embodied approaches to thinking into classroom settings for different ages. Shirah Rubin describes the use of movement in language acquisition in preschool settings. Rabba Daniella Pressner gives several examples of the importance of the arts in her elementary school in Nashville, TN. She extrapolates from the school’s experience about the possibilities and inherent strengths in bringing the arts–especially dance–into Jewish education. Professor Ofra Backenroth discusses her use of dance and dance analysis in college and graduate school classes. She gives examples of using dance as interpretation of text in order to heighten learning. The information in this section should inform many different teaching scenarios.

The next group of chapters gives examples of using embodiment theory to teach mathematics and science. Professor Roni Zohar focuses on bringing movement into the study of physics. She discusses how important movement is to the ability to study and learn over any period of time. Professors Alex Volfson and Yuval Ben Abu specifically use circus to study physics, for example, by using flow arts to describe a range of forces or fire hoop diving to discuss thermodynamics.

The last section of the book is where we explain our method of Sacred Arts. We begin with a review of the importance of movement in Jewish thought and sacred literature, including the Bible and liturgy. We contend that movement is part of the Jewish DNA; Jewish history, from the exile at the time of the destruction of the Temple through a history of expulsions, has included travel, the search for home, and a basic sense of transience. The concept continues in references to modern Hebrew poetry and folk dancing. In this chapter, we focus primarily on the more familiar art of dance to demonstrate these ideas. Though circus is typically less overtly discussed in conjunction with Jewish identity, history, and thought, given the historical connections in the previous chapters and given that circus is a movement-based practice, we see it as equally connected to Jewish communal narratives and ideology as dance.

With movement as an underlying structure, we then review our use of circus and movement to process sacred text by laying out the Sacred Arts method with examples of how it has worked. We also explicate into the underlying theories of Sacred Arts, calling on Biblical Studies, education theory, and Circus Studies.

Most of this research has been done in conjunction with the Academy for Jewish Religion, and thus the examples are connected to Jewish texts. That said, I believe the same method can be used with any literary text. Maybe next is Circus Tolkien Arts? Circus Foucault Arts? The research has only just begun… While practice as research, practice-based research, and other similar approaches are blowing up in the circus world, they are commonly using circus to study something about circus. This approach is also primarily practiced by highly skilled circus artists. There is a significant dearth of using circus to study seemingly disparate subjects and done so by complete amateurs. (3) The book aims to help rectify this shortage while providing the tools needed for others to find their own unique pathways of study.

(1) I say circus Sacred Arts because there has also been Sacred Arts research via dance, fine art, and others. (2) While this may seem like an unusual or farfetched reading to some, while God’s omnipotence is clear, there is good support to question God’s omniscience in the Hebrew Bible. (3) One must certainly direct people to Camilla Damkjær’s book “Homemade Academic Circus: Idiosyncratically Embodied Explorations Into Artistic Research And Circus Performance.” While she is a self=described “professional amateur,” she also uses circus to study a seemingly disconnected subject, Western Philosophy. Images are courtesy of the author....

Do you have a story to share? Submit your news story, article or press release.