Warm-Ups for the Circus Artist, Part One

Imagine you’re about to start warming up before your circus class. What will it look like? How long will you do it for and does it look the same every time? In this two-part blog post, we’ll be delving into all things circus warm-up.

I’m really excited to be getting this conversation started here on Circus Talk because getting a warm-up right can definitely limit your chances of injury and set you up for a more fruitful training session or performance. In part one, I will lay out the context of what a warm-up is and explain why and when we should do it.

In part two, we will look at the main components of the warm-up and how it can be carried out taking age, training status, skill/conditioning level and preferred discipline(s) into consideration. Video content will supplement part two, which will show different circus practitioners (students/recreational participants and professionals) performing warm-ups. Since there are so many ways to do them, differing in their intensity, duration, type and recovery period etc… these articles will attempt to pull together some of the vast array of warm-up styles to inspire you.

What is a warm-up?

Let’s kick off with a definition. I like Hendrick’s characterisation of a warm up as “a period of preparatory exercise to enhance subsequent competition or training performance.”(1)

In a nutshell, it must fulfill two primary objectives:

- To warm you up

- To increase preparedness for the activity you’re about to undertake.

The warming up bit

Exercising when warm is a good thing. As far back as the 1940s, investigators discovered that the capacity to carry out work is enhanced in warm body conditions. (2)

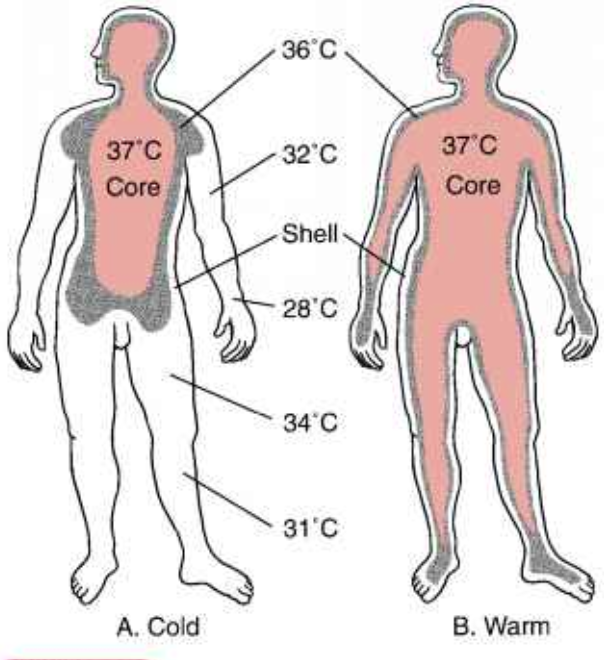

Lucky for us, humans are homeotherms (able to maintain a constant body temperature), which turns out to be very helpful when undertaking intensive exercise. But here’s the catch — sometimes there can be a large temperature difference between our core temperature (Tc) and our shell temperature (Ts). Think how cold your cheeks feel when you’re outside on a blustery winters day but how the blood pumping out of your heart still stays warm. (See Fig 1).

Tc is carefully controlled by our brains (average around 37°C / 98.6°F at rest) but Ts is influenced heavily by the external environment. When it’s cold, blood flow is diverted away from the skin, arms and legs and toward the core, and vice versa under hot conditions. The difference between Tc and Ts is usually only around 4°C at rest but can exceed up to 20°C in extremely cold environments. (3 |4)

With regard to warm ups, this means that your warm up should be longer when you’re in cold conditions and can be shorter when you’re in warm or hot conditions.

Increasing preparedness (body and mind)

So why is warming up our body beneficial?

As soon as you start moving your body through the warm up phase of exercise, thermoregulation kicks in as the body senses you are getting hotter. It will begin diverting more blood to your periphery — hands, feet, arms and legs. This has the effect of increasing your skeletal muscle temperature.

Warmer muscles = happy (more effective) muscles, especially for circus activities:

- it enhances muscles contractile properties (you can contract them more easily)

- increases muscles extensibility (you’ll feel more flexible and supple)

- increases muscle tensile strength (more difficult to break them under tension)

- enhances overall coordinated movement potential. (5/6/7/8)

Mental preparation

The warm-up may also be beneficial in allowing circus practitioners to mentally prepare/rehearse for the skill that is to follow. All professional performers that I work with have a very defined warm-up protocol which they consider an essential part of their pre-training/performance routine, and investigators have shown that the use of such pre-performance routines is a defining characteristic of successful Olympians. (9)

Stimulating your brain function

Remember: your nervous system is the master control system of the body coordinating and controlling every bodily function — from heart rate, breathing rate, blood pressure, body movements and so much more.

The brain receives information through movement and good quality movement is critical for optimal brain function.With each heart beat, roughly 25% of the blood flows to the brain and 90% of the brains energy is used in processing and maintaining the body’s relationship with gravity. (10 ) The brain weighs in at around 3 pounds (1.3KG); and the staggering thing is that although it’s only 2% of your body weight, it consumes 20% of the oxygen. (11) This means that if we are battling with pain, feeling a little tight or sore, or in bad neck posture from spending lunchtime on Instagram, the brain has to expend more energy in trying to correct that. Warming up therefore allows you to iron out some of those postural wrinkles and achy parts of your body so that your brain can concentrate its efforts on more complex movement and performance tasks ahead.

The brain receives information through movement and good quality movement is critical for optimal brain function.With each heart beat, roughly 25% of the blood flows to the brain and 90% of the brains energy is used in processing and maintaining the body’s relationship with gravity. (10 ) The brain weighs in at around 3 pounds (1.3KG); and the staggering thing is that although it’s only 2% of your body weight, it consumes 20% of the oxygen. (11) This means that if we are battling with pain, feeling a little tight or sore, or in bad neck posture from spending lunchtime on Instagram, the brain has to expend more energy in trying to correct that. Warming up therefore allows you to iron out some of those postural wrinkles and achy parts of your body so that your brain can concentrate its efforts on more complex movement and performance tasks ahead.

Should stretching be a component of your warm-up?

The short answer is yes. The long answer is – it depends on what type of circus activity you’re about to do. Some circus disciplines such as aerial hoop, contortion, and rope may need flexible joints to ensure large ranges of motion are available. By decreasing muscle stiffness and ‘loosening-off’ the joints you can better prepare the body for the extreme ranges of movement to follow. The proviso here is that the supporting muscles also need to be prepped so you’re not too floppy and loose. Indeed, one of the arts of warm-up is finding the balance between looseness of joints and just the right tension and suppleness in the muscles.

Disciplines such as trampoline and teeterboard for example, may focus less on stretching and more on preparing the muscle for fast contractions and joints for high load.

Disciplines such as trampoline and teeterboard for example, may focus less on stretching and more on preparing the muscle for fast contractions and joints for high load.

Furthermore, we should think about how much load or strain you will put yourself under when in those positions, when transitioning from one position to another or doing specific tricks:

Think about what your physical requirements are.

Are you basing someone? Do you require oversplits? Do you hang in “twisted grip” from one arm? Will there be a lot of impact load? Will you need to grip a lot? Will you need to balance on your feet or your hands? Do you need to hold huge amounts of body tension? And so on and so forth…

In sports science, there is a concept called “needs analysis” — the process of determining what qualities are necessary for the athlete/sport. Translate this into the circus setting. Take time out and do an in-depth analysis of what physical qualities are most valuable in order for you to perform your discipline well. It may highlight and give clues about where your warm-up and training focus should be. Think for example:

- about all the main positions you require for your chosen discipline(s)

- about your fitness and physical capacity requirements (aerobic/anaerobic/metabolic, strength, flexibility, endurance, power, balance, etc.)

Take a look at the clip below of some research we did with Middlesex University which managed to capture the g-force around the shoulder joint of of a professional straps artist, Augusts Dakteris.

We measured a whopping 5 g-force of deceleration force – the same amount of force as a formula one race car driver experiences at peak lateral force in turns! I’d say that’s a pretty strong argument for a shoulder warm-up, wouldn’t you?

If you’re about to take your body through it’s full ROM available and overpress past this, then it’s logical to prepare the body for this task. If you skip this preparation part and push your body to the extreme – you increase the risk of overloading the body’s capacity to withstand that stress and it can fail (causing injury of some kind). (12/13)

When should you warm-up?

It may sound obvious, but if you leave too much of a gap between your warm-up and the actual main exercise, you’ll nullify most, if not all of the benefits. Several studies have consistently shown this across multiple sports. The benefits will have almost completely abated after around 20 minutes of inactivity. (14)

To summarise, the main objectives of a warm-up are:

To summarise, the main objectives of a warm-up are:

- To raise shell body temperature (predominantly warming muscles to enhance their function)

- To move the body systematically through larger ranges of motion in preparation for athletic movement.

- To find an emphasis according to your discipline

- To gradually introduce to more challenging/complex movements

- To enhance mental and neural preparation

In part two, we will explore what to include in your warm-up and how to structure them.

Photos courtesy of Daniel Nogueira, Circus Physiotherapist for Perform HealthReferences: (1) Hedrick, A. Physiological responses to warm-up. J Strength Cond Res 14: 25–27, 1992.; (2) Asmussen E, Boje O. Body temperature and capacity for work. Acta Physiol Scand 1945; 10: 1-22; (3) Gisolfi CV, Mora F. The Hot Brain: Survival, Temperature and the Human Body. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000:1-13, 94-119, 157-63, 171-4, 191-215.; (4) Folk GE, Riedesel ML, Thrift DL. Principles of Integrative Environmental Physiology. Iowa: Austin and Winfield Publishers, 1998.; (5) Bishop, D. Warm up II: Performance changes following active warm up and how to structure the warm up. SportsMed 33: 483-498, 2003.; (6) Safran, M, Garrett, W, Seaber, A, Glisson, R, and Ribbeck, B. The role of warmup in muscular injury prevention. AmJ Sports Med 16: 123-129, 1988.; (7) Stegeman, DF and De Weerd, JP. Modelling compound action potentials of peripheral nerves in situ. II. A study ofthe influence of temperature. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 54: 516-529, 1982.; (8) McHugh MP, Magnusson SP, Gleim GW, Nicholas JA. Viscoelastic stress relaxation in human skeletal muscle. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1992: 24: 1375–1382.; (9) Orlick T, Partington J. The sport psychology consultant: analysis of critical components as viewed by CanadianOlympic athletes. Sport Psychol 1987; 2: 105-30.; (10) Dr. Roger Sperry, Nobel Laureate. (11) Clark D. D. & Sokoloff, L. (1999) in Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects, eds. Siegel, G. J., Agranoff, B. W., Albers, R. W., Fisher, S. K. & Uhler, M. D. (Lippincott, Philadelphia), pp. 637–670.; (12) McHugh MP, Kremenic IJ, Fox MB, Gleim GW. The role of mechanical and neural restraints to joint range of motion during passive stretch. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998: 30: 928–932.; (13) Magnusson SP, Aagard P, Simonsen E, Bojsen-Møller F. A biomechanical evaluation of cyclic and static stretch in human skeletal muscle. Int J Sports Med 1998: 19: 310–316.; (14) Cunniffe, Brian; Ellison, Mark; Loosemore, Mike; Cardinale, Marco. Warm-up Practices in Elite Boxing Athletes: Impact on Power Output. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research; January 2017: 31:1: 95–105....

Do you have a story to share? Submit your news story, article or press release.