Soundtracking Circus Creations: A Checklist and a Case Study

From July 3rd to 13th 2018, over twenty thinker-doers from a dozen countries, all practitioners and scholars of contemporary circus and/or other performing arts, converged onto Montréal during the Montréal Complètement cirque festival to participate in Concordia University’s intensive summer graduate seminar taught by Prof. Louis Patrick Leroux and titled “Experiential learning in Contemporary Circus Practice: Methods in research-creation, action-research and participant observation.” For two weeks, they attended lectures and seminars in the mornings, then in the afternoon, had studio time to work on their presentations or to attend participant-observation sessions as part of a larger research project, and of course, they attended performances in the evening.

In addition to their brief research-creation presentations, the students each produced two to three blogs during this period. We are offering a selection of those blogs. Some are candid, heartfelt, others analytical, some are critical takes, others are musings on students’research. They give a snapshot of what was on people’s minds during the summer intensive.Prof. Leroux and his teaching assistant, Alisan Funk, have also contributed original material to complement the students’ blogs. Check back every Friday until the New Year for an updated article from one of the participants!

Are you a musician who would like to compose for a contemporary circus creation?

Are you a contemporary circus artist or director who would like to work with live music?

Are you a bit hesitant to reach out to that other person because you are not sure whether the worlds of music and circus can meet?

Fear not, for now there is…this blog post!

My name is Loes van Schaijk, musician/educator based in Prague, originally from the Netherlands. Although I have seven years of experience as a music teacher at the Circus Arts department of Codarts Circus Arts university in the Netherlands, I never wrote music for the circus or performed on stage with a circus production myself until this summer. I would like to use this blog as an opportunity to share some of my experiences and thoughts for those who are interested in what goes on in a musician’s brain. I invite readers of this blog to share their own experiences with music and circus in the comments, because obviously just one case study is not going to lay down any golden rules, and it would be great to collect multiple perspectives here.

A Checklist

Ideally, a musician and a director who are going to work on a project together will already be familiar with each other’s work and they know that they are a good team and/or that they are a perfect match for what this project demands artistically. In reality, it can and does happen that they are brought together by chance or circumstance and still have to get acquainted. It is important to realize that getting to know another person takes some time; management specialists might disagree with me, but I don’t think it’s very beneficial in an artistic relationship to go for maximum efficiency. So, I would not necessarily recommend sending this checklist to a musician or director, discussing the answers over coffee and then getting straight to work. However, Idorecommend going for several coffees together and picking each other’s brain. I venture to guess that the musician’s brain will be occupied with these questions, some of which (s)he might already propose out loud to the director, some of which are part of a self-inquiry, and others might be saved for a later moment, if/when they will become relevant.

- Who are we (working with)?

1a. Self-check: what is my area of expertise and comfort zone?

What can I produce/execute quickly?

What is not yet in my skill set, but relatively easy to learn?

What would be possible, but more of an investment (time/money/energy)?

Where do I draw the line –-are there things I cannot or will not do and why?

1b. Who are my colleagues?

Will I be working with other musicians/composers?

What is their background?

How “invested” are they (time and motivation) in this project?

1c. Who is the (circus) director?

What is their background?

What is their experience with music(ians)?

What are their working methods?

1d. What agency do the musicians have?

Are the musicians fully “in service” of the director, executing their demands as precisely as possible?

If so, when can a musician use their right of veto (for artistic or logistic reasons)?

Or is there a collaboration in which the creative contribution of the musicians is equal to that of the director?

- What is the (artistic) concept?

What is the performance about?

What are the sources of inspiration for this performance (visual moodboard, inspiring music, literary texts etc)?

What type of movement material (and/or circus apparatus) is the director going for?

How does the concept dramaturgically translate to music?

- Which parameters for the music can be established in advance?

Does the director want live or recorded music?

Does the director want the musicians to be visible on stage or not?

Will the music be amplified or not?

Which instruments will we use?

Which genres of music are preferable?

Will the circus artists be making music as well?

How many minutes of musical material is needed?

Will there be moments of silence?

Will the score be compiled or through-composed?

Does the director want us to make completely new compositions, arrangements of

existing material, and/or to play existing recordings from their own database?

What type of soundtrack is called for: “songs,” a soundscape, or….?

Will some form of technology be called for? If so, is there a specialist involved?

What does the director absolutelynot want?

- What are the working conditions/logistics?

How much time is there for discussion between the directors and musicians?

Which mode of communication is preferred (meeting, phone, Skype, email…)?

How much time is there for joint rehearsals (director, musicians, artists)?

How much time is there for the musicians to create and work out musical material (“homework time”)?

In what space(s) will the musicians work?

What space will the performance be in?

Can the musicians safely store and transport their gear?

Is there a tech specialist or sound engineer?

Are the expectations realistic regarding the working conditions? If not, what are the consequences?

A Case Study

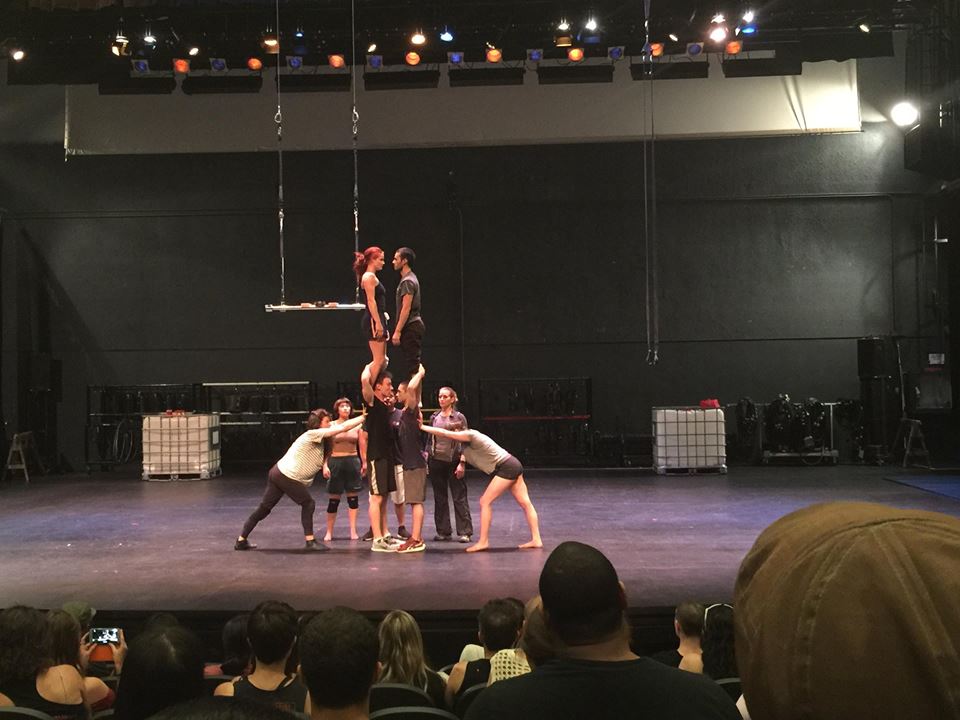

This July, at Concordia University in Montréal, three directors with different backgrounds worked with seven students from the École National de Cirque (ENC) and their coaches in the context of the three-year research-creation project, led by Louis Patrick Leroux,Poetics of Contemporary Circus: A Dramaturgy of Writing in (and of) the Movement.In this context, the research-creation itself was considered more important than any “result” (public performance/show/presentation or “rehearsing” for that). ComposerNick Carpenter was contracted to create the soundtracks for all three pieces, and I had the honor and the pleasure to assist him. Nick Carpenter is a Montréal-based playwright, pianist, and composer. He has a lot of experience composing for the theatre; however, this was his first circus project. When we were first introduced and we exchanged some music and ideas (via email and Skype), it was immediately clear that we were “on the same page” and that we would collaborate very well together.

Some numbers, just to get those out of the way…

There are no general guidelines on how much time is needed to compose music (for circus) and how much that should cost. That completely depends on the individual (their status, the quality of their work, their way of working, their experience, their gear, how much in demand they are, or how badly they need the job…) and the context of the project (can they re-use material they have already written or will everything be original, do they have to learn a completely new skill, is it in a genre they are familiar with, will it require several instruments and musicians or can it be done by one person on one computer, etc). That being said…

Very roughly, I would usually budget that one minute of music needs three hours of work (exploring, composing, practicing, recording, editing, mixing, etc.). That is excluding rehearsals, meetings etc. For the Montréal project, which was basically 10 days of creation with three teams, leading up to 3 x 10-minute presentations of works in progress, this would be my estimate:

Creation time: Three teams x 10 minutes of music x three hours of work = 30 hours

Rehearsal time (with directors & artists): Three teams x seven days x two hours = 42 hours

Meetings one-on-one with directors, debriefings, etc.: One hour x 10 days = 10 hours

Run-throughs & presentations = Six hours

Transport between spaces, set-up & build down tech/equipment = One hour x 10 days = 10 hours

Total = 98 hours

Preparatory communication via email and Skype started approximately 6 months before the intensive rehearsal period.

Team One – Michael Watts

The director of Team One was Michael Watts, who is from a dance background (e.g. Eastman – Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Dave St-Pierre) and has worked with ENC before as a guest teacher/director.

From the beginning, Michael clearly stated that he was very particular about the kind of music he wanted. He thought that Nick’s& my musical style would differ too much from his taste, and because of the project’s limited time frame he said he would prefer to work with recorded music of his own choice. Nick and I made it clear to Michael that we did not want to force ourselves upon him; we would be happy to work with him, but would respect his decision if he chose not to. On the first day of creation, Nick and he had a very productive three-hour long talk; Nick described it as “fun!!” and “quite intimate.” In this talk, Michael asked Nick to reflect on the sounds of the artists in their apparatus: not literally, but in a more abstract, musical way. Abstraction was an important theme: Michael wanted to avoid narrative and theatrical demonstrations, and instead was more interested in how they could work purely from the movements of the bodies. He also wanted to avoid creating sounds that suggest visual images of the sound source (the material object that produced the sound) or the musician making the sound. He would be looking for a sort of drum sound, but one that did not conjure up a picture of a drum or of somebody hitting a drum. He asked us to record natural sounds and then “bastardize them completely.” This turned out to be a very difficult assignment, especially since Nick and I are most comfortable working acoustically. An electronic musician, programming sounds based on sinus waves and so on, might have been much better suited to approximate Michael’s aesthetic. Putting effects on sounds might seem like an easy fix, but to do it well is quite a skill. The sound easily gets muffled and becomes dead, which is not what Michael wanted. He wanted the sounds to be powerful, precise, determined, as if they could penetrate a body. However, this assignment forced us to do a lot of exploring, going outside of our comfort zones, learning new skills and new approaches to find solutions.

The challenge for the composer is to trim it down, not so much to please the director, but so that the music does not crowd the stage or overshadow the artists; and at a level where the composer can still stand behind their own work and does not need to worry that the audience will find the music boring or sub-par.

Some key words that came up in talking about the concept were “the shivers”: Michael wanted the audience to go into space and have a trippy experience. He shared that he was a raver in the ’90s and showed us some of his (very cool!) visual artwork based on vintage bodybuilder pictures enhanced with bright ’90s-style colors and patterns. He said he was interested in the amoeba-like movements of the students very slowly and organically moving as a collective. At the same time, he was interested in the human body as a machine that can mechanically repeat the same movement as long as it is programmed to do so. These descriptions inspired us to create musical motifs. Sometimes we got a bit carried away; for example, Nick created a piece based on arpeggios that were repeated but never exactly the same – that was Nick’s interpretation of the amoeba. Michael did not like this piece, because it was too heavily loaded with (musical) information; the fact that the music was always changing might have been nice in concept, but it did not really work for him as he pictured it with the movement. Nick, not the type to get easily frustrated, did not mind at all and kept adapting the piece. He enjoyed the puzzle of what music the director is was imagining internally–cracking the code. For me, it was interesting to watch these men work together, as it is not the first time that I have noticed a discrepancy between what a director thinks is good music for the stage (often leaning towards “minimal”) and what a composer thinks is acceptable work (usually this means plenty of chord changes, unexpected turns in melody, interlocking rhythms and other things that make it quite the opposite of minimal). The challenge for the composer is to trim it down, not so much to please the director, but so that the music does not crowd the stage or overshadow the artists; and at a level where the composer can still stand behind their own work and does not need to worry that the audience will find the music boring or sub-par.

Michael tried to help us by sharing some recorded music with us that inspired him for this project, for exampleEmptyset and the music for Hofesh Schechter’sIn your rooms. As a composer/musician, I have mixed feelings about directors sharing examples. On one hand, it definitely helps to get a clearer picture of what someone wants to hear. On the other hand, it can also be a bit daunting (although it is obviously never the director’s intention to intimidate the composer.) But imagine: here we are, just 2 people with acoustic instruments and a limited amount of time, trying to emulate something that has been meticulously produced by who knows how many people with who knows what budget in who knows what kind of studio and over who knows what period of time. If the director actually expects you to create something equal to that or even better, they are guaranteed to be disappointed and the musician is guaranteed to feel like a failure. So, it is important to be communicative about the reason why you offer these “inspiring examples” and to make expectations transparent(and realistic).

Michael also asked us if we could help the students sing something chant-like. He asked the students to translate the sentence “I need more sleep and healthy food” into Spanish, which became: “Necessito dormir mas y comer sano.” I was overjoyed, because helping students to sing on stage is my main competency and comfort zone. The students seemed to be happy as well; they were very generous with their voices, singing loud and strong, and they kept on singing backstage after rehearsal (and so did the coaches!) It was a nice, funny, but also musically interesting moment in the piece that was appreciated by the audience. I was happy that Michael didn’t worry to much about what it looked like on stage, so the students were allowed to stand in choir position, so that I could conduct them,and Nick could come on stage to support the male voices. If this were to become a real show, it might have been nicer if the students were able to do it without my (or Nick’s) guidance, which I think they would be able to pull off if there were more time to rehearse.

In the end, I think it was a great experience for all three of us. One of my favorite moments was when Michael was sitting with us at Music Headquarters and exclaimed: “I get to work with musicians and with circus artists… I feel like a magician!”

Team Two – Jesse Dryden

Jesse Dryden is from a clown background and has done a lot of work with youth (Circus Smirkus, Cirque du Monde etc.)

He is experienced in working with musicians and responded positively to the news that he would be working with us. He made a conscious effort to include us in the process, always inviting us (and also the coaches) to participate in the warm up games, making it easier for us to connect to the circus artists as well, making us feel like we were all part of one big group. If he needed to direct his focus to the artists, he would say something like: “Now musicians, you can go off the stage and do musician things.” It was very pleasant for us to be called upon when needed, butalso to be clearly dismissed when we were not needed, so we were not left wondering, but could always spend our time efficiently. Jesse gave us some particular assignments to work on, provided us with the information we needed and then gave us a lot of freedom to work it out. He also thought of ways to integrate the musicians into the stage image and included the double bass in the story board. We felt very appreciated and comfortable in this project. It was a perfect mixture of work and play that we looked forward to every day.

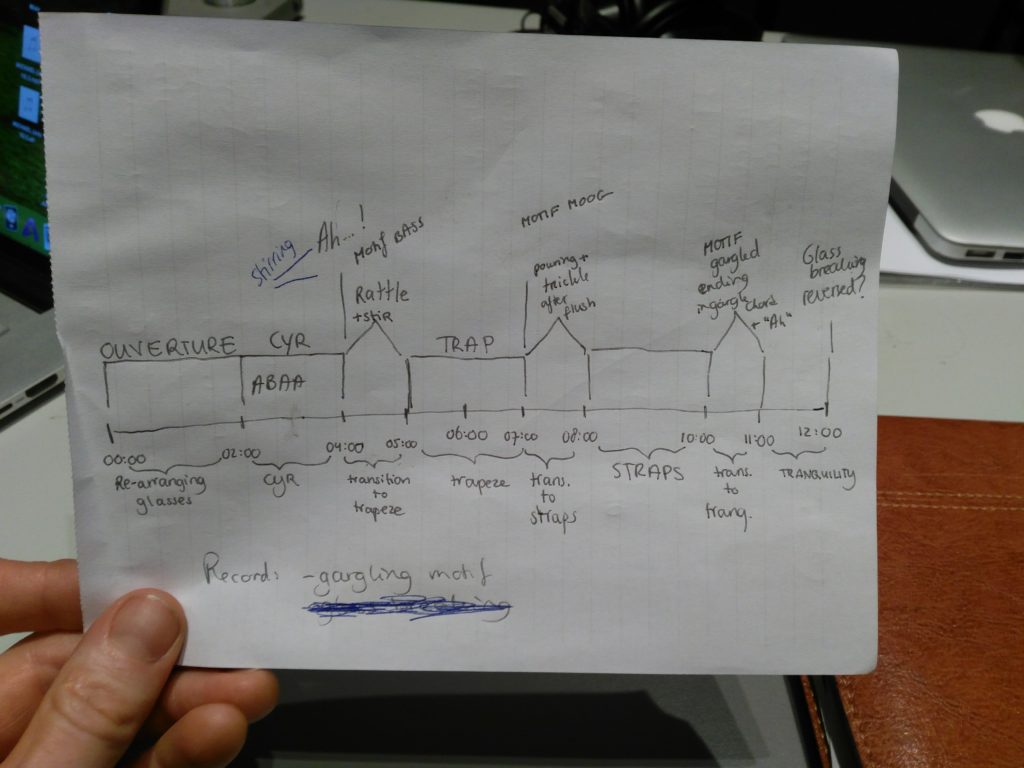

Jesse explained to us that his concept always starts with a mundane object, in this case a glass of water. Then, he starts to think about what the object means or could mean, and how this could translate into circus. The first thing to realize when the object is a glass of water, is that there are actually two things: glass and water. Both of these have been inspirational. On the first day of creation, the artists explored all kinds of sounds with water and glasses that Nick recorded: gargling, pouring water, tapping on a glass, rolling it… Nick made a rhythm out of the sounds and added a bass line so that it became a five-minute piece of music. It was so good that it became the main theme of the piece, and we would use the bass line as a motif for what Jesse calls “carryover music” (for the transitions).

One of the assignments Jesse gave us was to take a few glasses, fill them up with varying levels of water, so that they could function as an instrument for the artists to play. We discovered that an empty glass sounded like an E and at its fullest it would produce an Ab. We marked the water levels on the glasses so that five notes of the Ab scale could be played: Ab, Bb, C, Db, Eb. We made four of these sets. When we presented this to the artists (Jesse: “Don’t drink the instruments”), they didn’t know what to do with it at first. But when we explained that hitting any of them in any particular order (or simultaneously) would sound fine, as they all belong to the same scale, they started to improvise. Jesse asked them to form a circle with the glasses so that Louana, Angel, and Luisina could hit the glasses as Katherine was doing her Cyr wheel solo in the middle of the circle. Together, we thought of four different patterns they could play on the glasses. I later added a rhythmic bass pattern to support the tinging of the glasses. It turned out into a fun and energetic Cyr piece with a lot of potential for further development. For example, the movement of the artists who were tinging the glasses could be choreographed (when and how do they move from one glass to the next?); even though we did not show it in the final presentation, we did explore this a bit in the rehearsals.

I’m actually not sure if I should even call these sessions “rehearsals.” Jesse made it clear on several occasions that, as this was a research project and not a show production, he wanted to maximize the time for exploration and avoid rehearsing. I thought this was a good call for the artists, but for us it sometimes was tricky: when circus artists are working on a scene, they don’t necessarily need to run it from beginning to end. They can stop, do something else, and continue where they left off. As the forward motion of time is essential to music, this works differently for us. If we are working on a scene that we composed a song to, and the scene is stopped, do we stop playing as well? If this is at a random moment in the music, it is hard to pick it back up again when the scene continues. I spent a lot of time waiting, hoping that they would “sort things out” first and then just run the scene non-stop from beginning to end so we could match the music to it. But as soon as they had sorted out the scene, they moved straight to the next. Jesse might have expected us to just keep playing the music in a loop; but that is slightly unsatisfying to me, as part of the magic of playing live music to a circus act is matching it to cues and making sure the arrangement fits, so that you start together and end together. If you don’t run the scene, you can’t find out if that works.

The relationships between the artists were based on the four stages of water:

- Collection – Embodied by Luisina, German wheel – Solid.

- Evaporation – Embodied by Katherine, roue Cyr – Frantic, uncertain, hesitant but playful.

- Condensation – Embodied by Louana, Washington trapeze – Stoic, focused, fragile, shaky.

- Precipitation – Embodied by Angel, straps – Trickling down, cleansing, breathing.

The characters were explored in the four solo moments of the artists with their apparatus, but more so in the transitions between them. Jesse explained that each stage of the water cycle has its own language. The moment of transitioning from one stage into the next, of “pouring one vocabulary into the other,” is a moment when we see the difference and commonalities in (movement) language between the two artists who embody these stages. As the artists were exploring common movement material in duos, Jesse was consistent in his directorial cues: “This conversation is interesting,” he said when Luisina used the German wheel to pass a glass to Louana in the trapeze; “Hmm, we have already made this statement before, we need to change the phrasing,” he said to Katherine and Angel working with Cyr and straps.

On the 3rd day of creation, Jesse explained the concept of the water cycle and asked Nick and me to compose a musical motif for each of the stages in the cycle. Perfect timing, because we had the weekend to work on it. We each came up with a few ideas and worked them out into simple arrangements so that they had a simple structure (e.g, intro-A-A-B-A-coda) and so that we could play them together (e.g., first A: piano plays melody and bass accompanies, second A: roles are reversed, final A: we play the melody in unison). Over the next week, we adapted the arrangements several times, so that the structures were easier to lengthen or shorten as needed. The melody that I composed on the bass for “condensation” was ultimately played by Nick on the melodica, because its sound fit more to the concept of fragility for this particular stage. That worked out beautifully, because it made it possible for not only me, but also Nick (who was otherwise sentenced to sit at his piano on the side of the stage) to walk on stage as he was playing and interact with the performers.

Jesse is considering applying for funding to continue working on this creation and turning it into a full-blown production (so do not steal the ideas, please). I would be thrilled if I would get to be a part of that. On a research-creation level, I am curious to find out what it means to place my musician’s body on a circus stage, what I still need to learn about the circus vocabulary, and what common language we already have.

Logistically, making a professional show out of this would mean that amplification of the instruments (and on-stage monitoring) is a must; I had trouble hearing Nick, and it made me nervous to be center-stage not knowing if we were in sync or if I might be playing out of tune. So, I would advise Jesse to budget generously for sound: a sound engineer, monitors, wireless sets for instruments (and possibly voice). Wireless sets are expensive, but necessary if the musicians move around on a stage full of glasses of water.

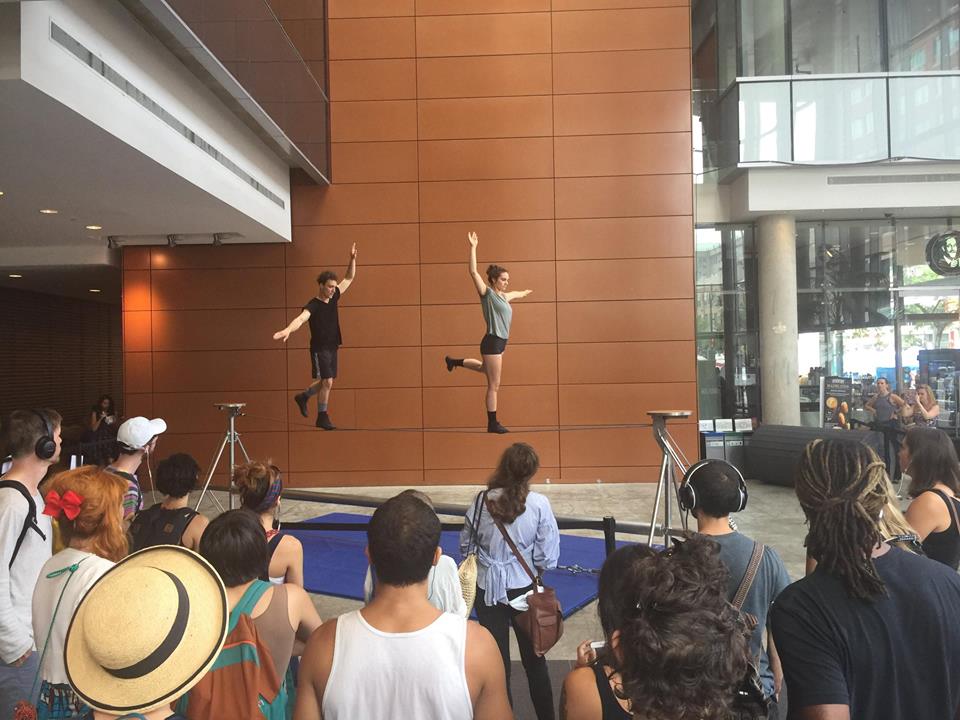

Team Three- Claudel Doucet

Claudel Doucet’s background is in circus as an aerial performer. She studied at ENC.

Her initial response to working with us composers was neutral. She was very busy with other projects, so she did not have a lot of time to meet with us. Another complicating factor was the fact that her presentation (including rehearsals) was to be in the EV Atrium, a large public space where it is difficult to make yourself heard because of the background noise and the echoing acoustics. The natural reverb of the place might have made it the perfect setting for a very pure and beautiful score of acoustic instruments, such as bass and voice, were it not for the fact that we were forbidden by the university to play any kind of music in the space! In the weeks leading up to the creation time, she became fascinated by the concept of audio walks and came up with the idea to broadcast the soundtrack on a web radio. Nick found a student at the music department who was willing to help them set up a web radio onMixlr. Unfortunately, the tech-savvy student was not able to be present for the creation and presentation, so the responsibility to get the technology to work ultimately befell Nick, who was a bit anxious about that. Nick asked for a back-up plan in case of spotty wi-fi, speakers or bluetooth earphones, so the artists could hear the soundtrack as well, and extra headphones and mp3 players for the audience members who do did not have a phone, but unfortunately there was no more room in the budget for these things, so we just had to take a chance.

When Claudel and Nick had their first meeting about the concept, she could already say that it would be about an ultimate state of focus or flow. She had some interesting sources of inspiration. For example, she is fascinated by watching professional sports such as soccer, because the athletes are “completely engulfed in the moment.” In the movement material and music, she was looking for a “repetition to reach a point of the obliteration of self.” She asked herself: “In moments of flow, are you completely yourself, or are you gone?” Nick translated that into our quest to make a soundtrack that gives the listener a sense of widening into a narrowing. We decided to make a 10-minute recording of the sounds that were already present in the space (which we would call the ambience). Then, we would carefully analyze this natural soundscape and attempt to recreate it with our own devices: in this case, the bass and the MOOG synthesizer. We would add the created layers to the natural layers and then gradually strip layers away, so that ultimately, only one layer would be left: the purest sound, more soothing than silence.

The more we listened to the ambience, the more familiar Nick and I became with those particular 10 minutes that during which I was walking around the space with the ZOOM recording device. There was a guy shouting to his friend “Ahmad!”, there was a girl who burst out in a song, there was the rhythmical sound of the escalator, a guy tapping his keys on the railing of the escalator, the ventilation system buzzing to a particular pitch, and so on. We created a fundamental drone on the MOOG on the same pitch as one of the natural drones in the space (a D). Then, we created another drone on the fifth (an A). Then we listened to the girl singing, and her melody had some Bb and C in it, which established D minor as the key for the piece. After making the two drones, I improvised on the bass as I was listening to the entire ambience track on headphones. I tried to either echo or underline what I heard. We listened to my improvisation and did some cutting: we kept the pieces that worked and muted the ones that were badly played, redundant, or otherwise not effective. I had wanted to create a few more layers and then execute the plan of “stripping away” layers, but it was already late, and we thought we should just send this draft to Claudel to ask her if she thought it was going in the right direction.

Claudel responded rather positively to our first draft. She had only a few, but some very clear, requests:

- She had written a text that she would like me to record, so that the score would function as an “audio walk.”

- She had a different type of “drone” in mind, something more like a tremolo. She played us a track byDirty Beaches as an example. She wanted this drone to be quite prominent throughout most of the track. The “shaky” quality of it was important to her, as it would resonate with the rattling of the tight wire and the tension of the artists’s bodies.

So, back to Music Headquarters we went. I recorded the text as she wrote it. When Claudel listened to the first recording of the text, she realized it sounded a bit patronizing, not so much because I did a lousy voice acting job, but because the text was a bit too strongly laced with sentences such as “I will guide you,” “Stay calm,” Don’t worry,” etc. She rewrote the text and was quite content with the second version. We made some slight adjustments in the timing (placement) of the text later but did not need to record it again.

We made the “Dirty Beaches drone” by recording tremolo bowing on the bass, copying the track and messing around with the copied track a bit. We placed it a few seconds after the first one so that it would create waves,and added a modulation effect.

On the day of the first presentation, everything worked. We got good feedback on the soundtrack; it seemed that it was successful in conjuring up the right atmosphere to support the circus. Nick just did a bit of mixing (adapting volume levels, equalizing the voice so that it sounded more clearer),but these were all minor incisions. As we had to juggle three projects, it was very pleasant for us that at a certain point we were more or less done with one of them.

On the day of the final presentation, the thing we had dreaded from the start actually happened: Nick was kicked off the wi-fi as he was broadcasting the track. People stopped hearing the soundscape just before the voice-over would ask them to come into the artists’s space and play a game of blinking the eyes for extended periods of time while walking around. Claudel noticed what happened and signalled the artists to jump right to the next part of the performance. It was a pity that it happened, but also a good learning experience: when working with technology, one must always have a back-up plan.

Although this project caused quite a bit of stress for Nick for fear that the wi-fi would fail (which it did), out of the three it was the one that demanded the least investment from us. We could not work with Claudel and the artists during rehearsals, so we could use this time for other things. Our meetings with Claudel were short and few. I had expected that this would cause me to feel the least attached to (our work for) this project, but funnily enough that was not the case. I found it very pleasant that Claudel was sparing, but clear with her feedback: she always had one or two points that we should work on because they were important to her, and the rest she would just leave in our hands. Of course, a composer loves creative freedom, but total carte blanche can also feel like the music is irrelevant to the director. It is good for the process if the director listens to your work and can tell you what they like and don’t like (and how they want you to improve that). Claudel did that in just the right proportion.

Conclusion

At the start beginning of this project, I was a bit afraid of feeling like a “gift horse,” as it was not the choice of the directors or the other composer to work with me. Fortunately, this fear turned out to be unfounded. Nick and I “clicked” from the first exchange of emails and our collaboration went smoothly throughout the process. We supported each other immensely and neither of us could have imagined doing this without the other. All three directors were very pleasant to work with, they showed us appreciation, and did their best to include us in the process as much as time allowed. I know this must have been hard as their time to work with the students was so limited already. In particular, Jesse made a conscious effort to connect us to the artists and coaches, which was very motivating – I think that in the end a collaborative and positive atmosphere always leads to the best results.

I was also suffering a bit from “imposter syndrome,” as I had no previous experience in composing for the circus, I had never been on the circus stage as a musician, and although I did study at conservatory, my major was in Music in Education and not in a particular instrument. This fear also turned out to be irrelevant. I felt like everybody involved took me at face value, wanted to get to know me and work with what I could offer. None of the directors seemed particularly interested in musical virtuosity per se. They were looking for music that was effective in supporting the scene, and from the feedback I got, it seems that I succeeded. My experience as a musician playing in bands and as a teacher and musical advisor at the circus school helped me in communicating with the directors and artists, in connecting the world of music and the world of circus, which ultimately seems more useful than the ability to produce many notes.

The three projects were each in their own way fulfilling on the level of research-creation.

- In Michael’s project, I did a lot of exploring (sound quality, timbre, rhythmical precision) and trouble-shooting. It was good training for the ears and the mind as it demanded sensitive listening and attention to detail.

- In Jesse’s project, there was a lot of space for composing and arranging. We created a lot of musical material (“songs”) and I felt a very satisfying sense of musicianship and ownership. Being on stage physically as a musician was also a great experience that I would love to continue researching.

- In Claudel’s project, as we had an acceptable first draft in such an early stage, we had a lot of time for polishing and publishing, creating a mix that was pleasing to us as a final product.

It is important to realize that the creation process of music and circus does not run completely in parallel.

Overall, the only thing that was lacking from the whole project was “incubating time.” If the process would have been stretched out over a longer period of time instead of being condensed into 10 days, Nick and I could have produced material in an earlier stage. The directors could have then tested our music with the artists, we could have observed their movement material, and we could have taken more time to make revisions.It is important to realize that the creation process of music and circus does not run completely in parallel. Once both the music and the movement material are roughly structured, then the next phase in the work would be to really bring both worlds together, to look carefully at cues, and transitions, and so on. We did not really get into that phase in this case. It felt really strange to me that, even though I had been observing the circus artists for a week, it wasn’t until some runs a day before the final performance that I actually got to see their movement material. In this project, Nick and I have created the music to the concept (i.e., the way it was explained verbally and with audio or visual examples by the director) but not to the embodied movements of the artists themselves. That felt like a missed opportunity.

Amplification equipment and a sound engineer who understands circus are vital to music for the stage. It is not self-evident that you can ask the musician to take care of it himself. Most musicians can muck around a bit with technology on a level that is good enough for the rehearsal studio, but if we’re talking about a professional production, you need a specialist on board.

I respect the reader who has made it all the way to the end of this lengthy blog. I hope that it has been helpful and informative and I am looking forward to reading your comments!

Related content: Circus Summer Seminar in Montreal, Meanwhile, Backstage…, What It Means When Circus Artists Take Part in Graduate Research Courses

Unless otherwise noted, photos courtesy of David Konečný. Bio photo courtesy of Phelim Hoey.

All Experiential Learning in Contemporary Circus Practice Seminar articles provided were edited with the help of Caroline Fournier-Roy, M.A. student of English Literature at Concordia....

Do you have a story to share? Submit your news story, article or press release.