Warm-Ups for the Circus Artist, Part Two

In part one we established the scientific basis for why warm-ups are an integral part of circus practice. To summarise, a well-constructed warm-up can mentally and physically prepare you for the demands of the circus discipline(s) that follow by:

- increasing shell body temperature

- enhancing metabolic reactions and blood flow to muscles

- enhancing oxygen delivery

- speeding up the speed of nerve transmission

- exploiting strength and power production

- preparing joints to move through larger ranges of motion and to withstand more stresses and strains

- set the tone, get the mind in the right place, establish a suitable tempo

- attend to any injury that may need special attention

Now let’s turn our attention to: Warm-up design

It is generally agreed in the sports science community that the overall physical objective of a warm-up is to allow the body to steadily adapt to the increasing physiological demands of the sport or activity that follows, yet stopping short of incurring excessive fatigue.

It traditionally starts with a low to medium intensity, continuous activity that warms up the temperature of the body.

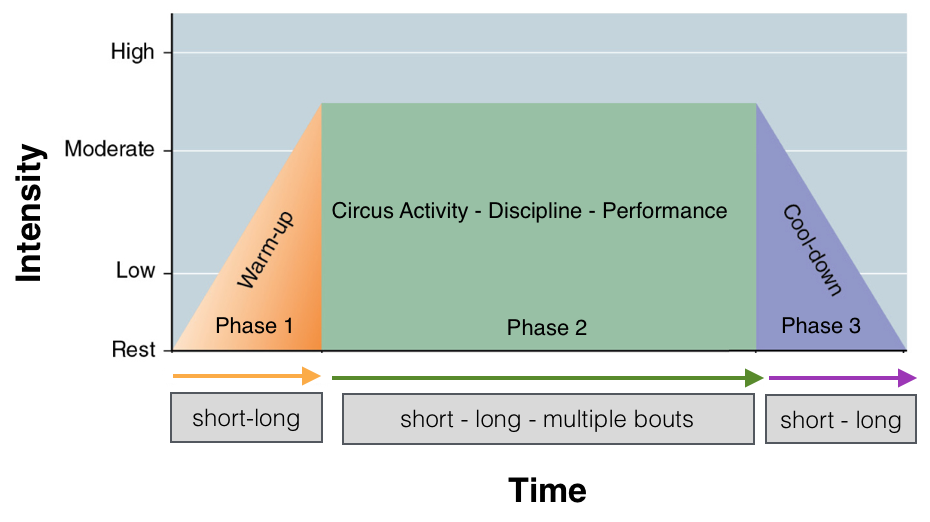

Figure 1. The traditional 3 ‘phases’ of the circus exercise experience – warm-up, main training/performance bout followed by cool down.

[Adapted from Bushman and Young (2005), Complete Guide to Fitness and Health].

Figure 1, represents the idea of a widely held view that the warm-up – phase 1 – should be a low to medium intensity, continuous activity that eventually fuses seamlessly into the main (circus) activity – phase 2.

In practice, does this ever happen? In reality, warm-ups are usually a little stop-start and depend on so many considerations including:

- space available (toilet cubicle or large training space)

- temperature of venue

- time available

- motivation

- teacher

- mood

- and many others

Over the past few months I have been discussing this topic extensively to get a better feel for what happens in training spaces, in schools and at performance venues. The main conclusion that I have drawn is that everyone seems to have their own warm-up method and philosophy of what works best for them. In one sense, this is great news as each one of them have identified specific preparatory needs for their own bodies, which may differ greatly to their peer or training partner. So no one size fits all I’m afraid.

It’s worth remembering that the circus arts encompass an extensive number of disciplines (Wikipedia lists over 130 different circus skills) using a variety of apparatus from hat manipulation to hair hanging; so it’s not surprising that one warm-up style would not be suitable to prepare you for every type of circus discipline. But why not?

The principle of specificity

This is the degree to which the warm-up stimulus is related to the subsequent circus activity. I like to think of it in this way: the main phase of circus training should act as a framework for which all other principles are built upon and should guide the decision making process for the type, volume and intensity of warm-up exercises.

Therefore,when selecting warm-up exercises, ensure that there is a correlation to what comes next.

Let’s consider what the physical requirements of doing a particular circus activity could be. Think right now if your current warm- up practice makes a positive impact on your main training phase? Think about the discipline specific movements required – does your warm-up mimic those movement patterns and demands that will be placed on the body?

General vs. specific exercises

General exercises will have a lower correlation with the principle circus activity but will still confer general benefits by activating muscles, limbering up the system, enhancing coordination, motor qualities, explosive strength, jumping, hanging, climbing, swinging and so on and so forth.

An example of general exercises for a ground-based acrobatic base could be: a variety of squats and lunges at various depths, in different directions, at different speeds, with light to medium loads. This will activate movement patterns necessary for stable stances and for steadying balance under load and will begin to tension the upper back and bring awareness into holding good spinal alignment in static and dynamic postures.

Squats and lunge variations contain some degree of general training to prepare the base for their basic role of varying balance stance postures under load.

Below are a list of some general exercises that begin to move towards the more specific for the ground-based acro basing requirements:

- form jogs

- knee hug walks

- skip with arm rotations

- quad stretch to RDL

- forward lunge walks

- backward lunge walks

- lateral lunges

- carioca

- knee highs

- skip for height

- lateral shuffles

- sumo squat

- straddle (middle, right, left)

- butterfly stretch

- figure 4s

- shoulder circles

- back/chest openers

- forearm looseners

- resistance band tubing exercises (rows, flys, rot. cuff, Y, T etc..)

- getting creative with battle ropes

- squat slams

- med ball / powerball throws/slams

- reverse lunge bottom up kettlebell press

- overhead barbell carry / balance

- Turkish get up

The exercises at the beginning of the list will confer general benefits such as, getting into right mental state, enhancing brain body connection, general loosening off, enhancing mindfulness of breath, checking in with the body and activating the different systems in the body readying for more intense exercise (see Table 2 for more exhaustive list below).

The closer you get to discipline/performance time, bring your warm-up activities closer to mimicking the actual movements you will be carrying out.

I would also suggest that the less experienced circus practitioner spends more time on specific warm-up as they need more time to rehearse, practice proper technique and refine movement skill in order to reduce risk of injury.

Warming up more specific technical skills for a ground based acrobatic base and developing specific adaptions required for the discipline could be: pressing inverted kettlebells above the head, or balancing a gymnastic box top above the head for example.

For beginners to intermediates, the warm-up phase is a great time to think about doing movements that mimic specific elements of the discipline at lower loads – to practice good movement patterns without incurring fatigue. It gives you an opportunity to develop more specific skill aspects at safe loads culminating in final technical execution of specific skills/tricks.

Professionals and more advanced practitioners will essentially just need to run through some of the actual skill/tricks themselves at near training/performance level as their bodies are at a closer state of readiness to perform at any given movement. They are more highly tuned machines and can safely work at near maximum or actual maximum loads/range of movements/jumps/impact etc…dependent on their discipline. This was my observations from having watched backstage prep at Totem, Cirque du Soleil and at Circ Cric last month. (See video of professionals warming up backstage before a big-top type show at the end of the article.)

So in conclusion, specific warm-up exercises should have higher correlation with the main circus activity you’re about to undertake.

Warm-up ‘cheat sheets’

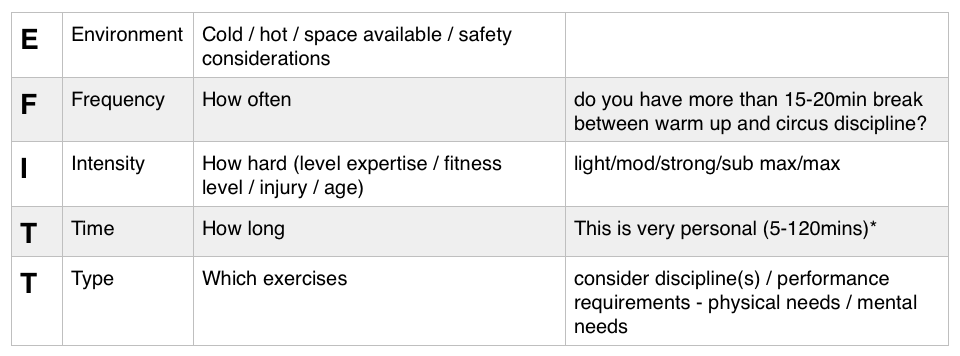

I’ve pulled together a couple of tables to help stimulate more detailed exploration into how you currently carry out or teach warm-ups. Firstly, see if you like the concept of using the EFITT principle? I think it’s a helpful reminder of some main considerations.

Table 1. The EFITT Principle for more structured, safer and more effective warm-ups

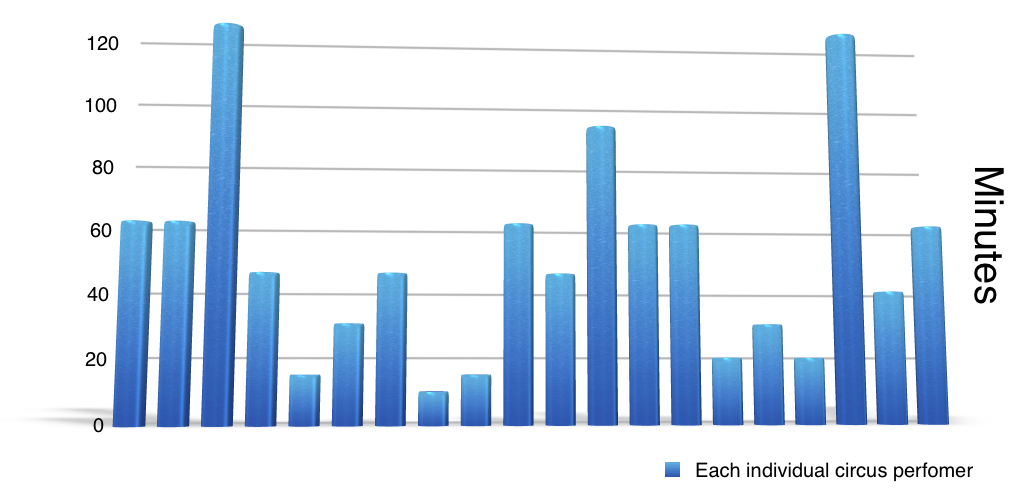

The “Time” or ‘how long’ should you warm-up for, turns out to be very personal! Below, in Figure 2 is a survey taken of 20 pro circus performers. The time range was enormous between 10 – 120 mins! What’s your average warm-up duration and what does it depend on?

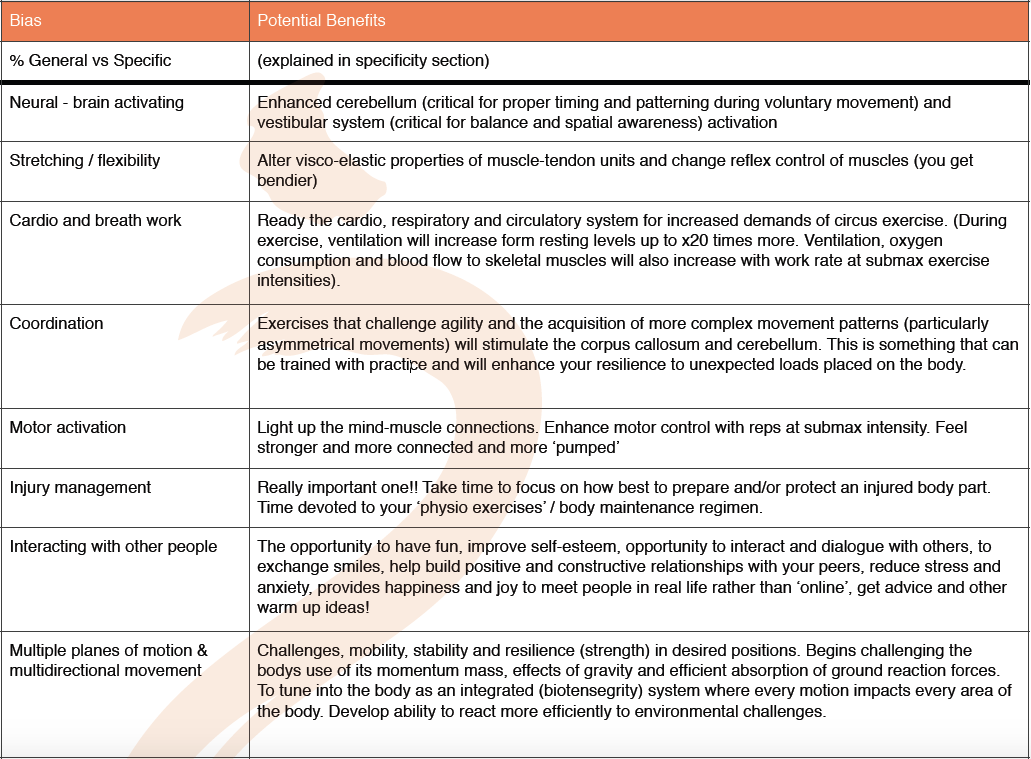

The “Type” or ‘ which exercises’ is the trickiest part; almost an art form you could argue. I pulled together some ideas to help us all out. It describes which elements you may want to develop during your warm-ups and how much time to devote to each. In reality, of course, we are often working on several things at once but I still think it can act as a useful reference guide to help focus you to develop a more thorough and safe practice. We’d love to hear from you and get your perspectives too (so please contribute in the comments section below).

Table 2.The different elements that can be biased according to the warm-up exercise type

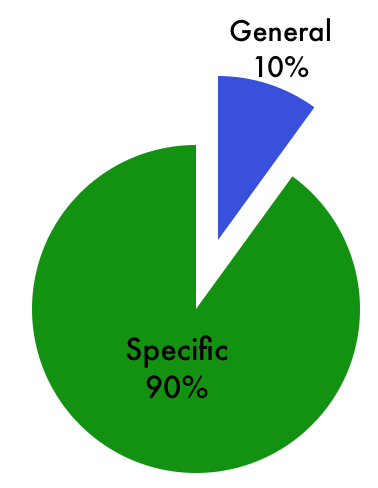

Whilst I was observing a contortionist warming up pre-performance, I was wondering how I could graphically represent what she had done for her warm-up phase. How general versus specific and what elements were focused on. This is what I came up with:

Figure 3 a. Pie chart representing percentage of time taken by a professional contortionist

doing general vs. specific warm-up before performance (10 minutes duration)

The contortionist spent the vast majority of time sequentially stretching out her body and gradually pushing into end of available range, followed by running through contorion positions and transitions. There was definite thoughtful process, connection of mind and body and an obvious thorough head to toe body checking in of how the body responded to being pushed to flexibility limits.

Figure 3 b. Pie chart representing percentage of time taken by a professional contortionist

for various elements of the warm-up phase before performance

Below is some video content to enrich the blog post a little further and to give you some more ideas for warm-up content:

A circus professional warming up on a ‘typical training day’

I had the pleasure to sit down on the couch with pro Cyr wheeler Felipe Nardiello to talk about warming up,

and after he kindly showed us his personal warm-up style.

It’s extremely specific, unscripted, emphasising contact with the wheel. It’s free flowing, full of improvisation and with motion in a variety of planes. As it progresses it gets more physical and technically demanding.

Circus Professionals warming up for a show – backstage access at Circ Cric, Montseny, Spain.

Here you can see a short clip of the typical backstage preparation and warm-up routines from the various artists in the big top pre-show with some basic commentary. Huge thanks to the great Tortell Poltrona, co-founder of Payasos sin Fronteras (Clowns Without Borders) for allowing us fly on the wall access.

Group warm-up in the circus school Rogelio Rivel, Barcelona, Spain with cyr wheel teacher Mark Glover

Here you can see one type of outdoor warm-up with a group of four, 1st year cyr wheel students with basic commentary.

Maximising your sphere of movement

I have also recorded a short video to explain the concept and importance of moving in 3 planes of motion, fusing flexibility work with ensuring good dynamic control.

Now over to you!

At Perform Health Ltd we would love to start compiling more examples of warm-ups for different disciplines in a variety of settings for the benefit of our wonderful circus community. There are literally thousands of ways of warming up and I’m sure we could learn from each other if we share and pool our knowledge. Send them in to me at: [email protected]

I’ll credit you and upload them to our Perform Health YouTube channel. Just make sure you ask permission first from the people warming up!

Feature photo courtesy of Daniel Nogueira...

Do you have a story to share? Submit your news story, article or press release.