Illuminating Identities: A Conversation with Lui L’Abbate, Trans and Non-Binary Lighting Designer

Lui L’Abbate (all pronouns) is a trans and non-binary multi-artist and designer from Brazil. Born and raised in Brasilia and Belo Horizonte, Lui works mainly with technical lighting and lighting design, but also acts, performs, researches, writes, and draws. They studied theatre at Brasilia University, did their Master’s in Theatre with specialization in lighting design and studied classical acoustic double bass in Brasilia’s Music School. Their research is about guerrilla and gambiarra (quick fix) as aesthetic creation methodologies, mainly in lighting design but also in acting and performing. In their free time, Lui enjoys watching TV shows, walking on the streets, and sending audio voice notes to people. Let’s hear what Lui is all about!

Megan Hill: What was your introduction to the Theatre Arts space and how did you get into lighting design?

Lui L’Abbate: I first did theatre when I was very young, I don’t even remember how old I was. But then we were doing a presentation for the whole school and I was so so soooo shy that I missed the performance and never went back to the school. Then, after many years, when I was around 13/14 years old, my brother (who is 2 years older than me) joined the school choir and theatre group. He invited me to join and I did, both.

That was when I fell completely in love with theatre and decided I wanted to do that for a living. So, I studied theatre performance in university, and around my 5th semester, I had a teacher who was a lighting designer and taught a subject about scenography and lighting design. At the end of the semester, he invited whoever wanted to accompany him in set-ups and lighting operations, so I went.

And that was when I fell in love with lighting design. Then he saw I was very interested and invited me to join the lighting laboratory of the university, and there I interned for a year or so until we had a major disagreement, me and the teacher, and I left the internship.

I was already completely in love with lighting and doing lights for people in the department, and it’s a profession that almost always has work because not many people work with it (at least not as much as acting or performing or directing, etc). So, I started to work with lights in 2015 and never stopped.

I am fully in love with my job and I’m very happy to be fulfilling a dream of mine to travel for work and meet many people and places. It’s been an amazing ride so far.

MH: You call yourself a multi-artist and designer. What does this title mean?

LL: For me, that means that everything I have ever done is a part of me and my job and how I see the world, how I interact with it, how I experience it, and how I live it. The fact that I have been writing for more than 10 years, the fact that I studied music, the fact that I draw, the fact that I act and perform and design light, everything influences everything. Because I also act, I design light and operate it like I do, and vice versa. That counts for everything. So, for example, I studied double bass back in 2014 and I don’t play anymore, but it’s still a part of me, and it still influences me and how I see the world and everything.

MH: What was one of the most memorable or eye-opening productions that you worked on in your early career?

LL: It was in 2017; the play is called Os Mamutes (“The Mammoths”) by Jo Bilac, a Brazilian author. It was the graduation play of the 2017 class of theatre from the University of Brasilia (UNB), and I was still an intern in the university’s lighting laboratory with my friend and colleague Iury Persan. We did this lighting design together and it was in a museum in Brasilia called Museu da Memoria Candanda (Candanga Memory Museum– “Mandango”/ is a person who was born in Brasilia).

This museum has closed spaces, but also open ones, and the play was all around the museum, so the public had to walk around following the acting. Our lighting design had to illuminate many rooms and we didn’t have much equipment, and our training supervisor didn’t want to lend us much equipment because of the place we were, because it’s a museum, it’s not made for the use of lighting equipment with a lot of power.

We operated the lights as a double and could not be seen by the audience, so as they moved around the space, we would also move around without being seen while also changing the lights. Our plan was this: we had two analog light tables—one was positioned in the auditorium, where the show started, and the other in one of the external areas, which we called the garden-corridor.

The equipment was already all arranged in the spaces of the scenes, disconnected from the sockets or connected but with the circuit breaker turned off. The operation worked like this: the show started in the auditorium, and one of us was already there to operate the light for the first scene.

Meanwhile, the other was strategically positioned, waiting for the audience to leave the first scene and enter the second space to turn on the lights on the circuit breaker. While the public was watching the second scene, the operator in the auditorium disconnected the cables from the table and transferred it to the main hall, where the end of the show took place, and connected the equipment that was in another external area, which we called the bonfire-scaffolding.

After connecting the equipment for the scenes in the bonfire-scaffolding space, the same operator went to another light table to operate the scenes in the corridor-garden. After the public moved to this new space, the operator who was in the second room went to the main hall to operate the following scenes. While the public was in the scaffolding-fire scenes, the two operators connected the equipment inside the main hall awaiting the arrival of the audience.

The transition to the final scenes was made by the light that called the public to enter the main hall where the last scenes would take place. It was a whole dance between light, operation, scene, transitions, the acting/actresses/actors and the audience: a gambiarra (quick-fix).

MH: You are from Brazil but spent quite some time in Portugal. Can you tell us the main differences or similarities between working in the theatre space in both countries?

LL: I’ve been in Portugal for almost five years now and have been working there in lighting design. I also did my Masters in Lighting in Porto, but now I live in Lisbon. For me, the main difference between the two places and working in Brazil and Portugal is that in Brazil we try to help each other—even the cis hetero man, white or not, who doesn’t respect us so much will try and help, like they want to do their jobs and go home as fast as they can. And they don’t do it badly just because they want to go; they do it very nicely so they don’t have to do it again.

In Portugal, and Europe in general, people don’t try to help you as much. They will do their jobs but in their time, not yours or the production’s. The technicians from the theatres, and sometimes from festivals, take their time, and this annoys me very much because sometimes we don’t have time, or we need more time, and they always say no before they say yes.

The most excruciating experience I had was in a festival where we had one day to set up, rehearse, and perform. My design was almost done; they only had to do some cables for the LEDs, and we needed to set up the floor lights (after the linoleum and the scenography). I think there were two technicians and it took them three hours just to go around with DMX cables for the LEDs. This, for me, was torture.

MH: Can you tell us more about what the experience of coming out as trans and non-binary was like for you?

LL: It was a process very unexpected to me, I would say. It was something like some friends and people close to me started to recognize me as a non-binary person, and it started to intrigue me. Then people I didn’t know began to recognize me as a man or as a trans man, mainly because I always had quite a lot of facial hair even before the hormones, and since I moved to Lisbon in 2021 I started not to shave it because I wanted to.

I had already lived this process of not shaving, but mainly because I can be very lazy, and even remember a day when I was working in the educational service of a museum in Brasilia called CCBB (Cultural Centre of Banco from Brazil), attended by a school and children of many ages. I received a class of children around 8/9 years old and one of them asked me why I had a moustache. I told him that all people had hair, men and women, and he asked me what I was/am. I told him woman (back then I still recognized myself as a woman) and he just accepted it, and this was amazing to me back then.

So back to 2021. I went to Cape Verde to do a job and they saw me there as a trans boy, a person even came to talk to me about this and asked about hormones and I was like, “I don’t do hormones.” But then I started to date a non-binary person, and they really opened up my eyes.

I realized that I was always this, and always believed in this, I just didn’t know and didn’t have the words.

This person was very important to me. Despite the fact that we are not together anymore and we don’t really talk that much now, they made me see myself in a very beautiful way that I didn’t before.

They made me realize a lot of stuff about myself and how I wanted to be and to live. They made me curious about the hormones, and that’s why I started to take them. I don’t want to get to a specific place; I want to enjoy the ride and make people confused.

For me, the confusion is the part I love the most. To have a beard and wear a thong and a cropped shirt with painted nails and use the women’s bathroom, you know? My goal is to make people confused, haha, and now I am very happy to have changed my name and gender on my birth certificate—let’s see how Europe handles it!

MH: What does it mean for you to be an out and proud trans, non-binary person in the theatre and creative world you are a part of?

LL: For me, it’s very important to occupy this space because it can show people that they can be where I am, it’s possible. My dream is to recruit more and more people to the lighting area: if they are trans, even better.

MH: How do you deal with adversity or working with problematic people?

LL: It’s a very difficult question because I am that person who freezes when faced with a situation where I don’t know how to react. For example, when I’m being oppressed, I can’t always say or do something; it’s very hard. But I’m working on it and I’m strengthening myself with friends and loved ones to be able to react.

But when I can react, or when I am able to, I usually am very calm when talking to them—usually sarcastic also, unless the person really gets on my nerves by not doing something I asked for or when the technicians don’t do their jobs, for example; then I get stressed out and can be a little rude. But with immense finesse, hahaha.

MH: What was your biggest or most notable career achievement thus far?

LL: This is so difficult for me, to categorize my work. There are a few productions that I believe mark my work because of the circumstances, the people involved, and the repercussions of the work.

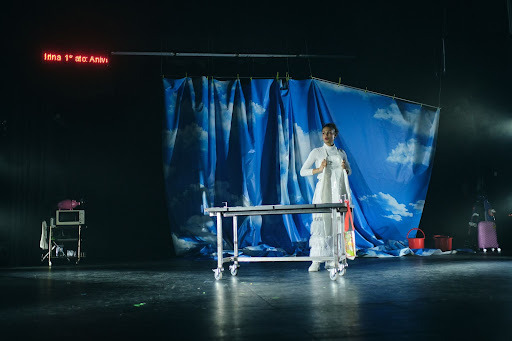

They were Viaduto from Renan Martins, which was a co-production from DDD, a festival in Portugal; 3 Irms from Tita Maravilha—she won a scholarship for this production, and it’s a very famous scholarship in Portugal called Bolsa Amelia Rey Colasso; this year’s Portuguese platform for Performing Arts, which I was part of with three works: Baquefrom Gaya de Medeiros, How to Kill Naked Women from Xana Novais, and Trypas Corassao the Opera from Tita Maravilha and Cigarra; and Puta Da Silvas’ concert at Arraial Pride 2022 in Praca do Comercio in Lisbon for many, many people.

MH: If you were given 30 seconds to talk to your 17-year-old self, what would you tell them?

LL: Try not to stray too far away from our mom, try to bring her closer to you and your circle despite it being difficult; I think that can help us in the future. Love yourself above everything and everyone—stay close to you and strengthen yourself with loved ones. And follow your heart: you know you and you know what you want, go for it. It will be hard but truly amazing, I guarantee you!

MH: What are some of the projects that you’re working on now?

LL: Right now I’m working on a few projects that are finished and we are performing again, Apocalypso and Viaduto, and in a few new projects, like the performance festival Terra Batida; a Portuguese theatre piece with Black people, Missao da Missao; and a queer non-binary immersion of light, body, and sound called Labia.

MH: What does it look like five years from now to Lui?

LL: Uff, that’s a difficult one… I just hope I am more financially stable than now, like, that I can organize my finances, and that I am happy with myself and doing lighting around the world—that’s my dream from my childhood that I now live.

I also hope I already have my van and am traveling around Europe, working and getting to know new places and people.

.

This article was originally published on TheatreArtLife.com. Written by TheatreArtLife Content Producer, Megan Hill.

Do you have a story to share? Submit your news story, article or press release.