Circo Criollo’s School

A fresh stop in Argentina led the Está Pasando project’s Miguel Manzano to a school that for four decades has helped Latin American circus spread everywhere from its own neighborhood to the most illustrious theatres of Buenos Aires. This is the story of Circo Criollo: the art, the school, and the family and artists who helped make it iconic.

Está Pasando continues its adventure of mapping the Latin American circus. It’s been almost a year since we began this journey, always with the support of CircusTalk. In this year, we’ve encountered many artists, companies, festivals, spaces, and circus events in South America. If you want to learn more about our project, you can check out the posts on our CircusTalk profile.

This time, I’m going to tell you a story about the origins of the new South American circus, about how the circus was the foundational stone of Argentine national theater, and about the family that, forty years ago, decided to share the secrets of the circus by founding the first circus school in South America in Buenos Aires: Circo Criollo School.

If you’ve read any of my articles, you’ll already know that I love to go off on tangents, so I’m going to start this story in the most unexpected place: a bar.

During our journey through Argentina, our van (La Cósmica, so named because it once belonged to an astronomy institute that used it to transport equipment) broke down several times, and we found ourselves stranded in the city of a friend who introduced us to a very skilled mechanic. Tired of constantly repairing La Cósmica, we decided to stop the trip for as long as it took to make everything work perfectly. That kept us at the mechanic’s for five months. We changed it so much that, after several changes—engine, clutch, carburetor, hoses, pistons, valves, and two shamanic rituals—we also changed its name to La Caracola. Now we’re slower, but we’ll go further.

I’m telling you this because during those five months in San Francisco with our friend Cuete, many things happened. Cuete is someone who never stops organizing circus events. In fact, if you want to travel through Argentina and have a circus show, you should talk to him. We participated in several events, performing and conducting Functional Juggling activities.

At one of these events, we met Roque Niklison, from the Circo Eguap company, and we coincided with them at the artists’ meals in a downtown bar in San Francisco. We talked for hours about a thousand circus stories, and among them, he told me about his alma mater: the Circo Criollo School in Buenos Aires. Before saying goodbye, he said, “You can’t leave Argentina without visiting that place. It’s the cradle of the new circus.”

So, I decided to go to Buenos Aires.

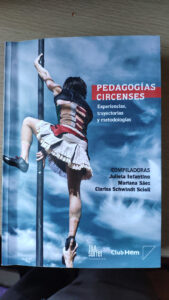

But before that, while we were waiting for our mechanic to fix the van, we made a stop at the Municipal Circus School of Rosario to give a Functional Juggling seminar and conduct some interviews with the school’s managers. During the interview, I had a conversation with Pablo Tendela, one of the founders. The interview was wonderful, and we shared many thoughts about circus. When it was over, he gave me a book:Pedagogías circenses, written by Julieta Infantino.

The book was a wonderful compilation of perspectives on the different ways of teaching circus in Argentina. And the first chapter was precisely about the person who started it all: Jorge Videla, one of the Videla brothers—the founders of Circo Criollo School.

The Circo Criollo

Está Pasando operates in the following way: at the various circus events we attend, I like to meet and converse with people. Sometimes the conversations are trivial, and sometimes they are profound. Sometimes someone mentions another person to me and ends with the phrase, “You have to meet them.” So that person stays in my memory, and I simply trust that life will lead me to them. And that’s how I met Gabi Videla. The difference is that several people told me about her before I met her. I believe that influenced how easy it was to find her. The more people tell me that I “have to meet” someone from the circus world, the easier it is for me to reach that person. Everything flows. Everything influences us.

I arrived in Buenos Aires in late August 2023. It wasn’t that long ago, but my feeling is that it’s been years.

My first stop, almost as if honoring history, was the Circo Criollo. In the city center, if Buenos Aires has one. The school is an old, tall warehouse with an aging façade and an entrance hall filled with memories of the Videla family. After passing through a corridor, a huge space opens up, which is the Circo Criollo School, founded in La Plata over 40 years ago.

The name of the school, “Circo Criollo,” is, in itself, a lesson in circus history. And, as I love to go off on tangents, I’ll tell you about it.

Buenos Aires is known for its rich theatrical tradition and is considered one of the cities with the greatest theatrical legacy in the world, with a large number of theaters and performance venues enriching its cultural scene. Currently, there are more than 300 active theaters. And this has been the case for centuries.

The Río de la Plata was the cultural gateway to Europe. Since the 19th century, immigration from Italy, Spain, Germany, and France has filled the streets of the Argentine capital with all kinds of artistic proposals and styles. In those days, the stages of Buenos Aires were a symbol of prestige for artists worldwide, the pinnacle of many careers.

In this context, both theater and circus coexisted, each catering to a different audience. One with its grand palaces, becoming increasingly larger and more exclusive, and the other with its tents, becoming more versatile and popular.

In the late 19th century, around 1880, José Podestá founded his Circus Arena company, which eventually changed its name to Circo Criollo. The concept of “criollo” refers to Argentine, gaucho, and popular culture. In the quest forcriollo essence, he decided to incorporate a “second part” into his circus show featuring the playJuan Moreira, which recounted the adventures of an Argentine gaucho who faced many hardships.

To interpret Moreira, a man who was criollo, who rode a horse, who acted, who sang, who knew how to dance and play the guitar was needed. And, above all, someone who knew how to handle a facón… — I have that man. It’s José Podestá, the clown Pepino. They called me. Gutiérrez arranged the pantomime. On the day of the rehearsal, the mime director, Mr. Pratesi, told me:

— José, they’re going to kill us tonight.

It was a triumph. Moreira was in the soul of the people. I put all my criollismo, my heart, my spirit, my love for the pampa into it. Since then, the cult of criollo courage had a symbol. How many times the audience identified with the gaucho’s drama! Persecuted by injustice! In Chivilcoy, a police officer, seeing Moreira cornered by the police force, leaped into the ring, with a blunderbuss in his hand, ready to defend him.

-Interview with José Podesta in the magazineCaras y Caretas,1939

That’s the end of the first part of the lesson. When I teach, I like to tell the story first and then explain it. Now I’ll explain to you, before continuing, why the impact of Circo Criollo was such that it ended up becoming a scenic format in itself.

It’s as if tomorrow, you created a show knowing perfectly well that the audience will love it. And it works so well that everyone wants to copy it. And with each copy, the audience grows. And so, your show becomes a pivotal point in the country’s culture. Some people consider the Argentine national theater as the evolution of Circo Criollo.

The model was simple. Imagine a circus, like so many others at the time. Many of them were ‘imported from Europe,’ often entire families of artists arriving from Europe by ship. But that’s another story. Circuses, as I mentioned earlier, reached a popular audience. Juggling acts, acrobatics, balances, clowns. The magic of circus. Then, José Podestá came along and decided that in his tent, right after the circus show, there would be a second part consisting of a popular theater play. That is the model of Circo Criollo.

The expansion was such that years later, there were hundreds of Circo Criollo circuses throughout the country. And in this way, circuses became the cultural transmitters of Argentina. Through the “second parts” of the circuses, renowned theater directors in the capital brought their plays to the small towns where the capital’s culture didn’t reach.

I don’t know about you, but I’m fascinated that once again, the circus becomes a tool for outreach that reaches where no one else does. Amazement reaches the villages, along with ideas. Nowadays, we turn on our devices and get a cultural and news overdose. But before, the closest thing to that phenomenon was the circuses that reversed the course of the Río de la Plata: nourishing themselves with capital culture and flowing into the small villages in the interior.

The Videla Brothers

“When we started teaching, no one accepted it. Our first enemies were our own; we were opening up a game that had been very closed until then. If you wanted to learn circus, you had to marry a circus woman or start driving stakes and follow the circus. We started the school, and they criticized us, threw us out of the circus. They told us, ‘You’re giving the game away to fools.’ Even my father didn’t accept it. He said, ‘You’re going to break a chain that has existed forever, and you’re going to take jobs away from all the artists, your brothers, your cousins.'”

-Jorge Videla, Circus Pedagogies, 2021

The book I was given at the Rosario circus school,Pedagogías circenses. Experiencias, trayectorias y metodologías, compiled byJulieta Infantino, Mariana Sáez, andClarisa Schwindt Scioli, was crucial for my research in Buenos Aires. In it, I found several perspectives on what I came to look for in Latin America: how do they teach circus here? From where? What’s the spirit of it?

While the book is heavily influenced by the realities of Buenos Aires, it gathers 16 viewpoints from individuals with extensive experience and backgrounds in circus education. The real gem at the beginning of the book is the posthumous writing of Jorge Videla, who, along with his brother Óscar, founded Circo Criollo and unveiled the secrets of the circus in 1980.

This first chapter is incredible because it intertwines Jorge’s memories, shortly before his death, with those of his wife Olga, who was recently interviewed by CIRCA Fotos Narradas. All with the support of their daughter Gabi, the current director of the school, who, almost inadvertently, inherited her father and uncle’s dream.

I spent a wonderful afternoon at the school, conversing with Gabi Videla and her mother Olga. I will share the interview I conducted with them shortly. In the meantime, I’ll share some of the things they told me.

The Videla family, like many circus families, has a scattered lineage, with ancestors from Chile, Mexico, Argentina, the Romani people, and more. This diversity is something I find beautiful in traditional circus, as it proudly showcases the variety of its heritage. I believe this occurs because each person in the circus world has a record, whether through their feats or because someone directly captured their story. This record is quite helpful.

I appreciate the concept of a living memory. I’m fortunate to have grandparents who are still alive, and my family shared many stories of our ancestors. Some are fascinating, like a grandfather who was a prisoner of war in the Philippines or a great-grandmother who nursed a renowned flamenco singer, known worldwide.

In the circus, all families have a living lineage in which, as Gabi told me, someone was the first to join the circus. There’s always a link from some great-grandfather who ran away with a circus to eventually establish their own. Every lineage has a starting point. That reminds me of Hermanos Castro Circus and its new traditional circus.

The Videla brothers were numerous, and many cousins and relatives also work in the circus today. Óscar and Jorge were acrobats, trapeze artists, jugglers, and clowns who decided to share the secrets of the circus at a time when Argentine circus artists were in high demand, and many were leaving the country. In the absence of local artists, they decided to follow in the footsteps of the Circo de los Muchachos (“Circus of the Boys”) and train street kids themselves, providing them with a trade.

This decision brought them strong opposition, both from their family and the circus community in general. Unlike the significant projects for democratizing circus education in the Soviet Union, with the opening of the first Russian circus schools in the early 20th century, in this case, the school was founded by two brothers. They had a clear vision and mission: to teach circus to all those who wanted to learn it. Simple and transformative.

Years later, Gabi recalls her father seeing a juggler at a traffic light and saying with a sigh, “How far I’ve come.”

Circo Criollo School

Circo Criollo School owes its name to the style of circus that existed in Argentina from the late 19th century well into the 20th. It was a tribute and a statement of intent.

Since its founding, the school has evolved and adapted, much like any circus. It began as a project that today we might call a “social circus.” Then, in the 1990s, with the help of Beatriz Seibel, it solidified itself as a professional circus school that has trained several generations of Argentine and international artists.

The curriculum consists of three years of training: the first year is general, the second allows you to specialize in your chosen discipline, and the third year focuses on creation. Upon completing your studies, you can consider yourself a well-rounded circus artist because, during the process, you are taught not only the techniques but everything you need to know about the circus, from setting up tents, applying makeup, performing on stage, and taking bows to making wise contract decisions.

This was the first circus school in the Americas, following the Russian tradition. It trained the generation of artists that has ushered in the new circus. As Jorge Videla used to say, “unintentionally, we have created a university” because many of the new circus schools and spaces in Argentina and many other places in South America have been founded by former students or students of former students of Circo Criollo.

There is still much circus to discover in Latin America. We continue on our journey in search of stories that connect us with the old, the new, and ultimately, the essence of Latin American circus.

All images provided by Esta Pasando. Image of Jose Podesta from Wikimedia Commons....

Do you have a story to share? Submit your news story, article or press release.